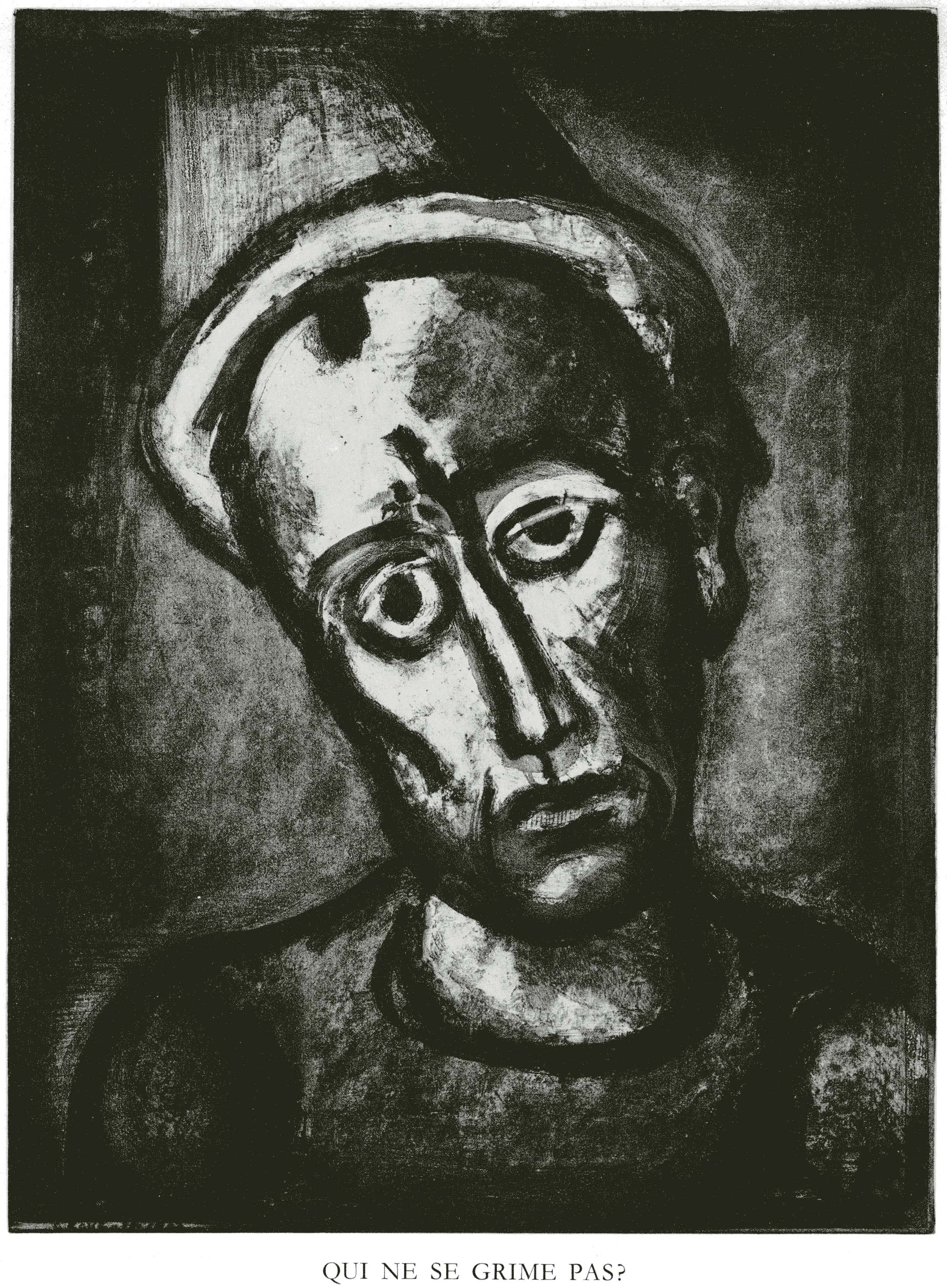

Miserere is Rouault’s most important graphic work. It comprises fifty-eight plates engravedbetween 1922 and 1927; and was published in 1948. Qui Ne Se Grime Pas? [Plate 8] is the only clown face portrayed in Miserere. ‘Se Grimer’ means literally ‘to make up’; but in the context of this image might also be translated as ‘Who does not wear a mask?’

The Rouault Catalogue Raisonné reproduces five original versions of Qui Ne Se Grime Pas? painted on printing proofs of the image. [Nos. 1590; 1590 bis; 1608; 1610 [the above] and 1611].

This version and No 1590 in The Indianapolis Museum of Art, are the most important and striking paintings. The Indian ink version [No 1608] is in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Miserere is the biblical prayer and plea for mercy. For Rouault, the clown was both a symbol of suffering and, with his ability to create laughter, of hope. He often portrayed himself in the guise of the clown.

The engraved Miserere image

Like a mighty bell tolling the Matins, Miserere brings forth a timeless procession proclaiming man’s inhumanity to man. No other artist, in the 20th century, has, in a single, engraved work, given such powerful, reverberating voice to the suffering and folly of man. It is a vision without compromise and for all time. The perpetrators of evil, whether by design or indifference, are set naked in the limelight – and so too are their victims.

Rouault considered his Miserere ‘An essential work’ and his most important graphic creation. It was conceived in 1912, the year of his father’s death. The 1914-18 war gave his images a terrible dimension. Through them he waged his solitary war against the senseless barbarity of the moment and the tragic tradition to which it belonged.

Miserere was executed in black and white between 1922 and 1927. No other colours could have conveyed the solemnity of its message nor its particular depth and richness. With tools he himself fashioned and applied in unique manner, he reworked, countless times, each plate, to attain through pure line and a vibrating fusion of tones and surfaces a profoundly expressive, luminous image.

Through these images and his accompanying words, Rouault speaks for the innocent and the solitary, the oppressed, the disposed; and the dying.

Despair drew Rouault to create his Miserere. Yet amid the figures of death and suffering, the proud and the powerful, the misguided, the corrupt, the foolish, the rigid and unbending, there is ‘Love’. And there is ‘Hope’.

In ‘To love would be so sweet’ [Plate 13] woman is ‘Love’.

‘Man is a wolf to man’ [Plate 37] precedes the instigators of war [Plates 38, 40, 49, and 51]. And the incredibly moving ‘This will be the last, little father’ [Plate 36] and ‘Wars, dread of mothers’ [Plate 42] herald its full disaster.

Often against a darkened landscape, cast in the shadow of Golgotha, stand the victims of man’s supreme folly.

‘Alone in this life of pitfalls and malice’ [Plate 5]; ‘The hard task of living’ [Plate 12]; ‘The prisoner is led away’ [Plate 18]; and ‘De Profundis’ [Plate 47] are heartrending cries of despair.

And yet……. ‘Tomorrow will be fair said the castaway’ [Plate 11]; ‘Sometimes the way is beautiful’ [Plate 9]; ‘In so many different domains, the noble task of sowing in hostile lands’ [Plate 22]. Each offers its glimmer of hope.

In Miserere – visually and metaphorically – light becomes dark and darkness light. ‘Who does not wear a mask’ [Plate 8]. ‘Sometimes the blind have comforted the seeing’ [Plate 55]. Nothing is completely what it seems.

Christ, portrayed in fourteen of the images, is for Rouault, the supreme symbol of suffering, love and therefore hope. And of man’s vital search for truth. ‘Qui ne se grime pas?’ the only clown present is Rouault himself ‘in make-up’, giving expression to these attributes.

What magnificent but sombre sound, mingled with notes of unspeakable tenderness, would emanate from a Miserere set to music?

And does some small part of each of us not reside in these timeless beings who parade before us? For finally, are we not all solitary travellers whose salvation, like that of the artist, lies – however hostile the soil – in sowing our grains of tenderness, light and beauty. And in becoming a part of that inevitable, mysterious and comforting solitude.

!['Qui Ne se Grime Pas?' [‘Who does not put on make-up?’] c.1930s](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_800,h_800,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy/ws-richardnathanson/usr/images/publications/main_image/14/rouault-qui-ne-se-grime-pas-.jpg)