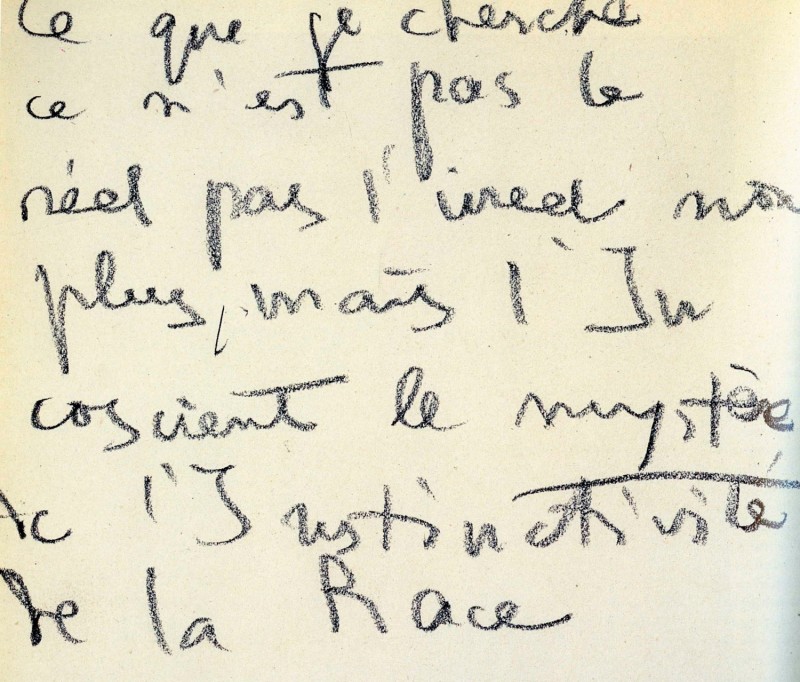

What I am searching for is neither the real nor the unreal, but the Subconscious, the mystery of what is Instinctive in the human Race.

—Amedeo Modigliani

If everything ever written about Modigliani were suddenly to disappear so there remained a single sentence to explain the essence of his art, it would be the above words, which he wrote in French, at the age of twenty-three, in a small sketchbook. The human face and form have, for thousands of years, been the artist’s principal subject, yet Modigliani depicted both in a way that will remain entirely his own.

Modigliani's handwriting in a sketchbook of 1907: Ce que je cherche ce n'est pas le reel pas l'ireel non plus, mais l'inco[n]scient le mystere et l'instrinctivite de la race.

Modigliani was a delicate child and suffered several debilitating bouts of pleurisy. At fourteen, he almost died of typhoid fever. His mother recalled that in his delirium, he spoke continually of paintings he had seen in reproduction and, in one nightmare, of missing the train to Florence to visit the Uffizi. At sixteen, he almost died from a severe tubercular hemorrhage. His early close encounters with death gave him a heightened sense that his life would be brief, and this quickened and intensified his ardent desire to create his own vision of beauty for the benefit of others.[i]

In 1901, some months after his near-fatal illness, he wrote from Rome to his artist friend Oscar Ghiglia:

I myself am the plaything of very powerful energies which are born and die. I would like instead that my life is like a very rich river which flows with joy upon the earth. . . . I am trying to formulate with the greatest lucidity the truths of art and life I have discerned scattered amongst the beauties of Rome; and as their inner meaning becomes clear to me, I shall seek to reveal and to re-arrange their composition, I could almost say metaphysical architecture, in order to create out of it my truth of life, beauty, and art.[ii]

That Modigliani should, at so youthful an age, be concerned with extracting, from the ruins of ancient Rome, timeless truths in order to “re-arrange” them into his own artistic vision makes this a particularly remarkable and moving statement of intent. Later that year, he again wrote to Ghiglia:

We others (excuse the plural) have different rights from normal people, for we have different needs which place us above—this must be said and believed—their morality. It is our duty never to be consumed by the sacrificial fire. Your real duty is to save your dream. Beauty too has some painful duties: these produce, however, the noblest achievements of the soul.[iii]

If we consider these letters together with the words he wrote in his sketchbook six years later, we can sense that Modigliani was searching for a visual form that fused the harmonious, lyrical energy of nature with the mystery and beauty he saw in human beings. But what, so early on, had inspired his philosophical, spiritual outlook, and thus his art?

Until the age of ten, Modigliani did not attend school. He was principally educated by his elderly French grandfather, Isaac Garsin, who, after his wife died, had come from Marseille to Livorno to live with his daughter Eugenia, Modigliani’s mother. Isaac was highly cultured and spoke several languages. He adored art, literature, poetry, and philosophy and gave his young grandson an abiding love of each. He also proudly claimed, through his great-grandmother Regina Spinoza Garsin, to be descended from the Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677). Over the years, he would have spoken to Modigliani about Spinoza’s belief that God, far from being a separate entity determining the actions and fate of mankind, is omnipresent in the workings of the universe, in all its manifestations. Modigliani’s “mystery of what is Instinctive in the human Race” is imbued with this belief. In all likelihood, he would have agreed with Albert Einstein, who, when asked to state his religious credo, wrote, “I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of all that exists.”[iv]

Isaac would have described to his grandson Spinoza’s simple, frugal way of life and utter indifference to wealth; his absolute integrity and courage in quietly pursuing “his truth” in the face of universal, even life-threatening, religious condemnation; and his acute insight into human nature, apparent also in his accomplished charcoal and ink portrait drawings. Isaac would have spoken of Spinoza’s seemingly humble livelihood in Holland as a master grinder of lenses for microscopes and telescopes, which enabled him to study the infinitesimal and the infinite and the intense affinities existing between them; and of how this helped inspire his unifying philosophy and deepen his awareness of man’s misconceived visual-mental perception of reality. And he would have emphasized Spinoza’s preeminent desire, through his philosophy, to enrich mankind. For the exceptionally intelligent and sensitive young Modigliani, Spinoza became an ever more vivid and heroic presence, heightened by their perceived ancestral connection.[v]

The art critic Gustave Coquiot recorded in 1924 that Spinoza had been one of Modigliani’s greatest literary passions. Inspired by Euclid, the structure of Spinoza’s posthumously published Ethics mirrors a geometric proof, citing geometric theorems to prove the logic of his beliefs. That these theorems were based on timeless, abstract forms of pure line would have intensified Modigliani’s deep sense of kinship with a man whose way of life and philosophy he so greatly admired. “Do I not have here the most meticulous, the most exact, the most cruel form of pantheism?” he remarked to Coquiot.[vi]

Upon arriving in Paris in 1906, Modigliani immersed himself in the rich diversity of art displayed in the city’s museums and pioneering art galleries, absorbing into the prism of his extreme sensibility art forms encompassing thousands of years: the elegant simplicity and symbolism of the Cycladic figure and face; the mesmerizing aura of Egyptian goddesses; the purity and majesty of Greek sculpture; the gentle humor of the Etruscans and noble austerity of Roman art; the sensual movement of Indian dancers; the otherworldly serenity of Buddhist art; the raw energy of the African artist’s portrayal of the human soul; the humanity of his own Italian artist ancestors, among them Giotto, Simone Martini, Michelangelo, Botticelli, and Titian; the pulsating vitality of Toulouse-Lautrec’s line and piercing characterization; Gauguin’s glowing mysticism; and the sheer beauty, richness of color, and intensity of Cézanne’s art. From each of these seemingly disparate sources, he took those elements in true accord with his own spiritual, aesthetic nature. All about him reverberated the battle cries of “Fauvism!” “Cubism!” and “Futurism!” but Modigliani had no interest in what he considered fleeting stylistic fads, for he saw himself as belonging to a timeless artistic tradition that venerated the unchanging beauty and mystery of human beings and nature.

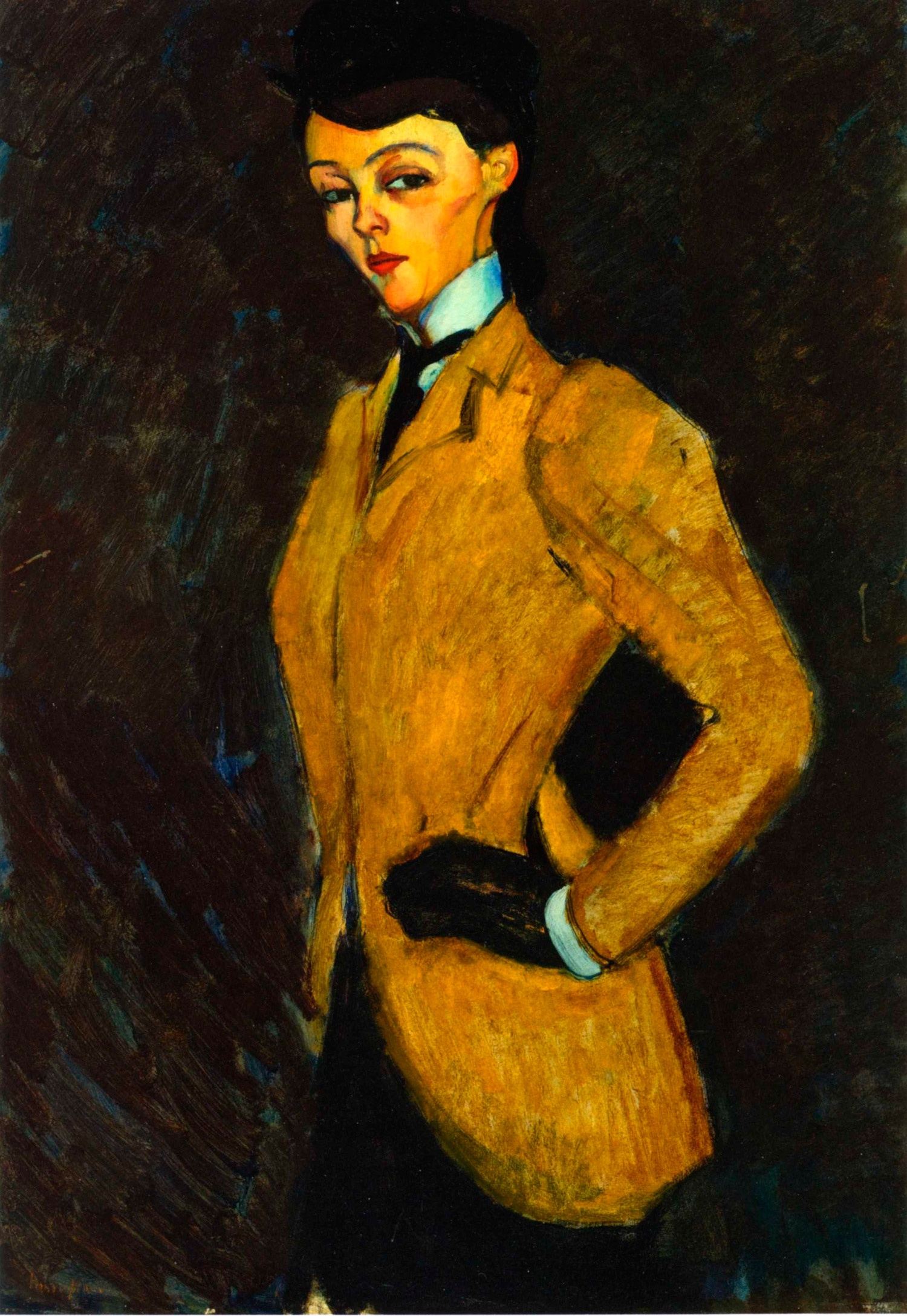

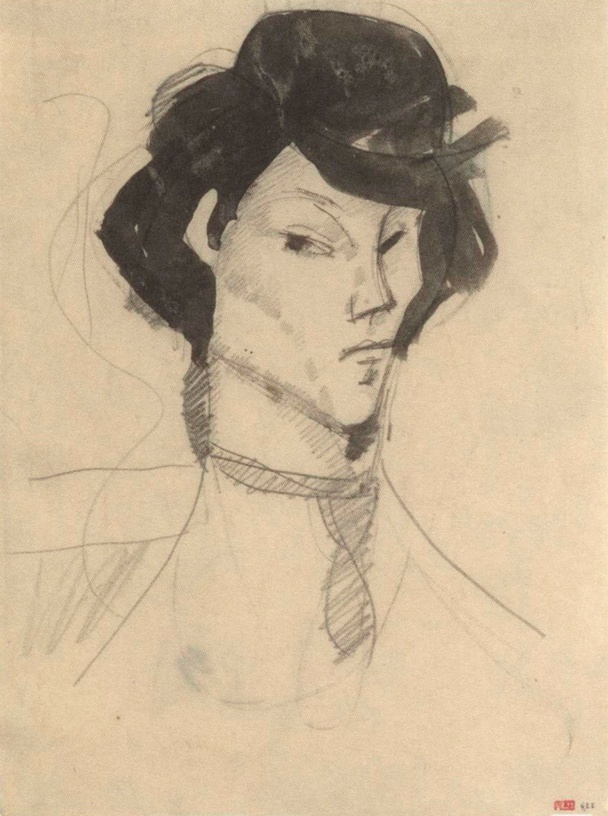

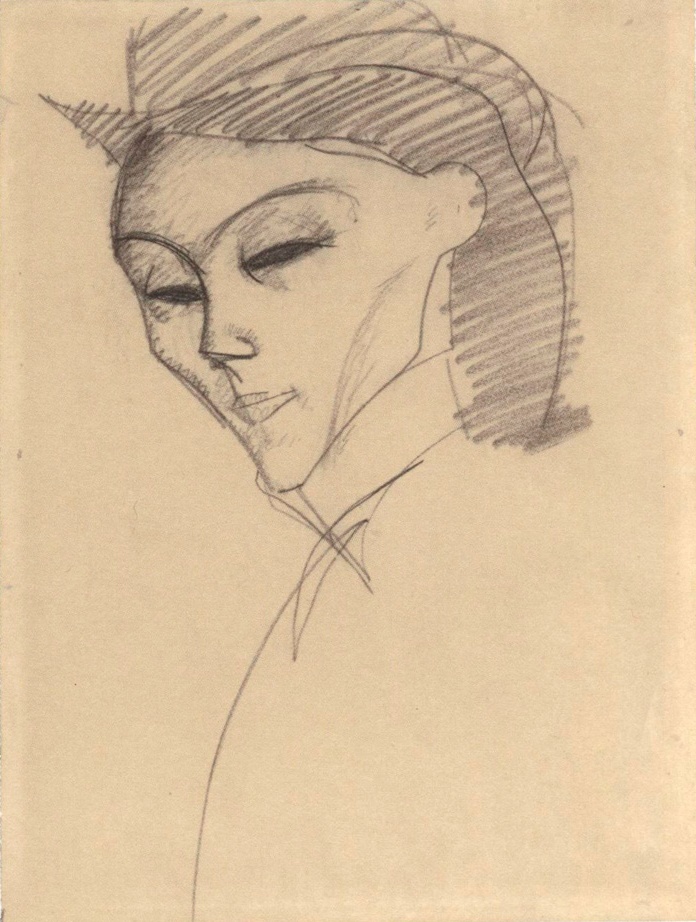

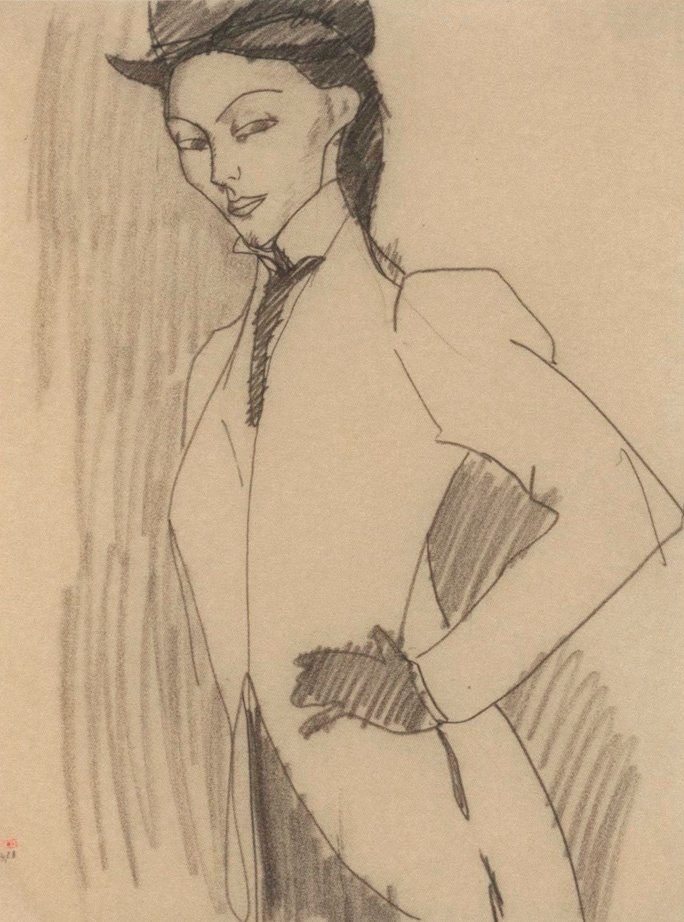

The Amazon, Modigliani’s 1909 painting of Baroness Marguerite de Hasse de Villers, the mistress of Paul Alexandre’s younger brother, Jean, is one of the artist’s most striking early portraits. Jean’s fascinating letters to Paul explain the baroness’s aloof, disdainful expression and imperious posture, which are progressively apparent in the Amazon studies collected by Paul. The tension between artist and sitter sets the picture apart from any other Modigliani portrait, giving it a particular character and power.[vii]

The Amazon, 1909, oil on canvas, 92 x 65.6cm.

Studies for The Amazon, 1909, black crayon on paper.

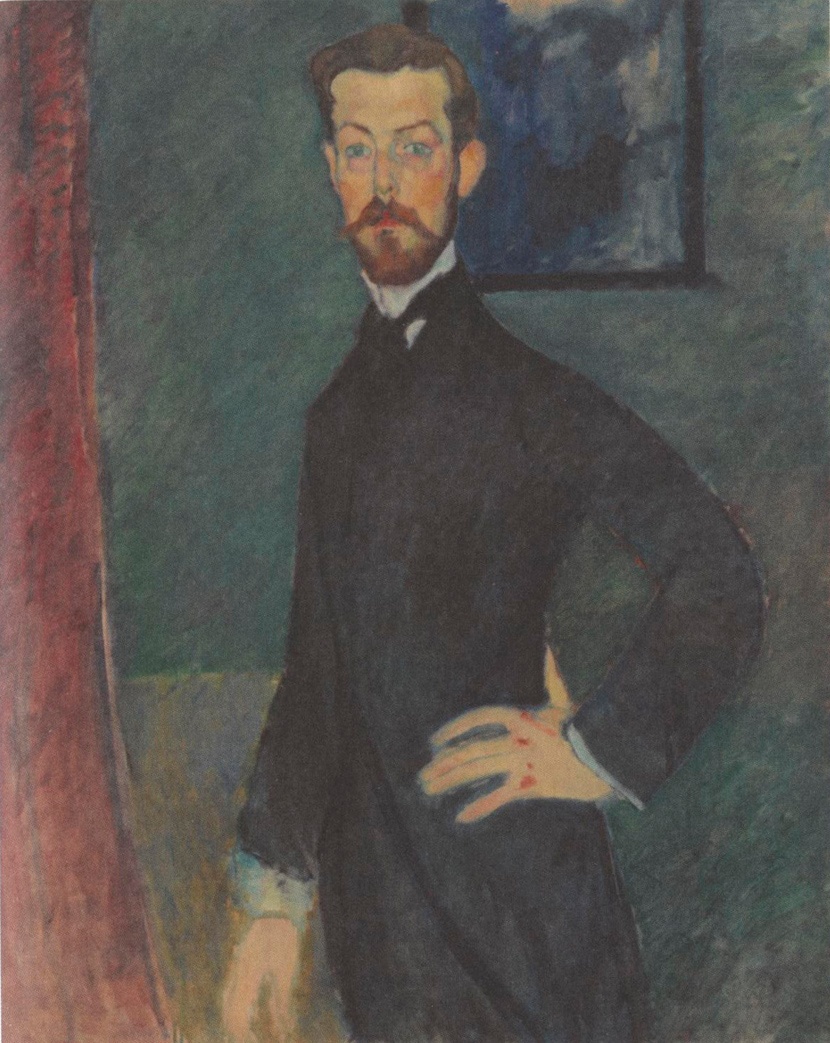

That same year, Modigliani painted three wonderful portraits of Paul Alexandre (see fig. 38 [x-ref to Klein fig]) as well as the poignantly beautiful Cellist, an homage to Cézanne. Yet, his desire to portray “the Subconscious, the mystery of what is Instinctive in the human Race,” compelled him to go beyond what he considered conventional portraiture—beyond “the real.”[viii]

From left to right: Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, 1913, oiil on canvas, 80x45cm; Paul Alexandre on a Green Background, 1909, 100.5x81.5cm.

Modigliani’s meeting with the great Russian poet Anna Akhmatova (1889–1966) in Paris, in 1910, during her honeymoon, thus occurred at a critical moment in his art. His first sight of her must have been electrifying, for he would instantly have recognized in her charismatic beauty, otherworldly presence, and tall, graceful body the physical and metaphysical embodiment of his vision.

From left to right: Moisei Nappelbaum, The Poet Anna Akhmatova, 1924; Anna Akhmatova Seated, c.1911

After she returned to Russia, they corresponded, throughout the winter. In 1911, she returned alone to Paris, and they became very close:

In 1910, I saw him very rarely, just a few times. But he wrote to me during the whole winter. I remember some sentences from his letters. One was: You are obsessively part of me. He repeatedly said to me: We understand each other. And often: Only you can make that happen.

He had the head of Antinoös, and in his eyes was a golden gleam—he was unlike anyone in the world. I shall never forget his voice. He lived in dire poverty, and I don’t know how he lived. He enjoyed no recognition whatsoever as a painter.

He was so poor that in the Jardin du Luxembourg we sat on a bench and not, as was usual, on chairs since you had to pay for them. He complained neither about his poverty nor about the lack of recognition, both of which were clearly apparent. He seemed to me to be encircled by a girdle of loneliness.[ix]

In her memoirs, Akhmatova described Modigliani’s love of Egyptian art:

He used to rave about Egypt. At the Louvre he showed me the Egyptian collection and told me there was no point I look at anything else. He drew my head bedecked with the jewellery of Egyptian queens and dancers, and seemed totally overawed by the majesty of Egyptian art.[x]

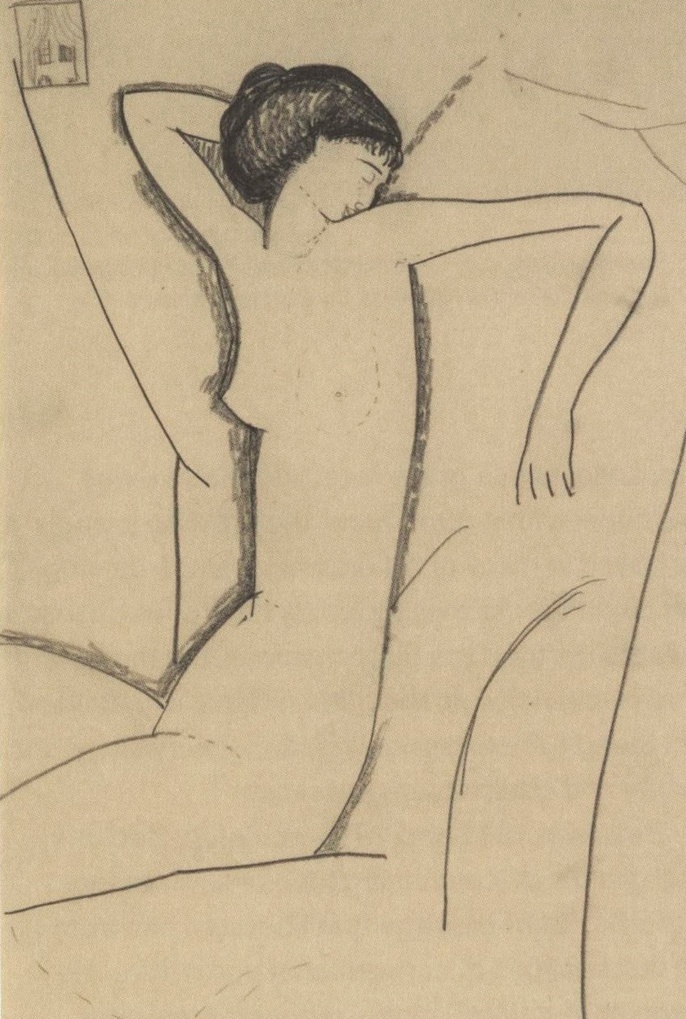

Given his profound admiration for other cultures, the sole plausible explanation for Akhmatova’s claim that he cared only for Egyptian art was her imminent return to Russia and the artist’s obsessive need, during their few precious weeks together, to study her as often as he could among the Louvre’s Egyptian reliefs and sculptures so he might more vividly portray her in their guise. For Modigliani saw in Akhmatova the same timeless, mystical beauty he adored in the Egyptian figures. In Standing Nude in Profile with Lighted Candle, the poet’s closed eyes and body poised symbolically, in an erotic trance, above a single lit candle leave us in no doubt of the spell she had cast upon him.

Female Nude with a Lighted Candle and Chandeliers, inspired by Anna Akhmatova, c.1911, Black Crayon on paper, 42.9x26.4cm

Akhmatova wrote of their deep love of poetry and each other:

Whenever it rained (and it often rained in Paris) Modigliani took with him a huge old black umbrella. We would sit together beneath this umbrella on a bench in the Jardin du Luxembourg in the warm summer rain; and jointly recite Verlaine, whom we knew by heart. We talked mostly about poems. We both knew a lot of French poetry: Verlaine, Laforgue, Mallarmé, Baudelaire. . . . And all around us raged cubism, all-conquering but alien to Modigliani. . . . He did not draw me from life but alone at home.

It astonished me that Modigliani could find ugly people beautiful and stick by this opinion. I thought even then that he clearly saw the world through different eyes to ours. Everything that was fashionable in Paris and which attracted the most enthusiastic praise did not even come to Modigliani’s attention.

Once when I went to call on him, he was out. We had apparently misunderstood one another so I decided to wait several minutes. I was clutching an armful of red roses. A window above the locked gates of the studio was open. Having nothing better to do, I began to toss the flowers in through the window. Then without waiting any longer, I left. When we met again, he was perplexed at how I had entered the locked room because he had the key. I explained what had happened, “But that’s impossible,” he replied, “they were lying there so beautifully.”

For a long time I thought I would never hear anything from him again . . . but I was to hear a great deal of him.[xi]

In Modigliani’s last postcard to Paul Alexandre, sent from Lucca on May 6, 1913, he wrote, “Happiness is an angel with a grave face.” Akhmatova was the “angel with a grave face” the artist so lovingly portrayed in many of his drawings, stone carvings, and paintings. As they movingly testify, his obsessive quest to portray “the Subconscious, the mystery of what is Instinctive in the human Race,” crystallized and found full expression in Akhmatova’s poignant beauty and otherworldly presence.[xii]

Between 1911 and 1913, sculpture became Modigliani’s all-consuming focus—a necessary, cathartic rite of passage that liberated him from the last vestiges of conventional portraiture. He chose light-colored stone, more ethereal and elemental than wood or bronze. Yet, while many of his sculpture-related drawings depict “spirit beings” rather than humans, others, like his later sculptures, mirror Akhmatova. One has only to compare the almost primitive Latner head and other early,roughly hewn heads with the exquisitely beautiful, refined carvings inspired by Akhmatova, some of which are direct portraits of her, to see her transformative effect upon his art .

Left to right: Head, c1910; Head, c.1910; Head of a Woman , c.1911

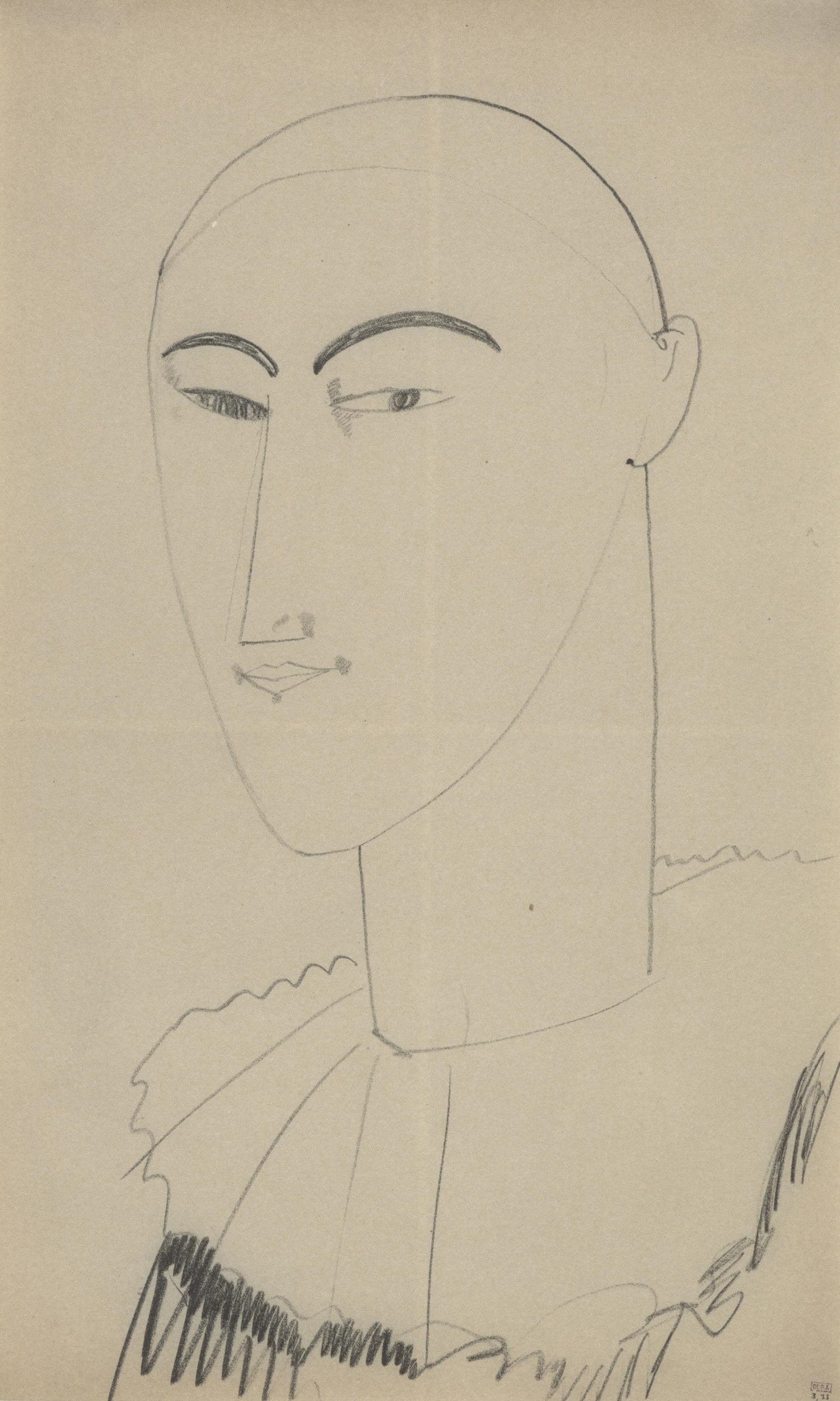

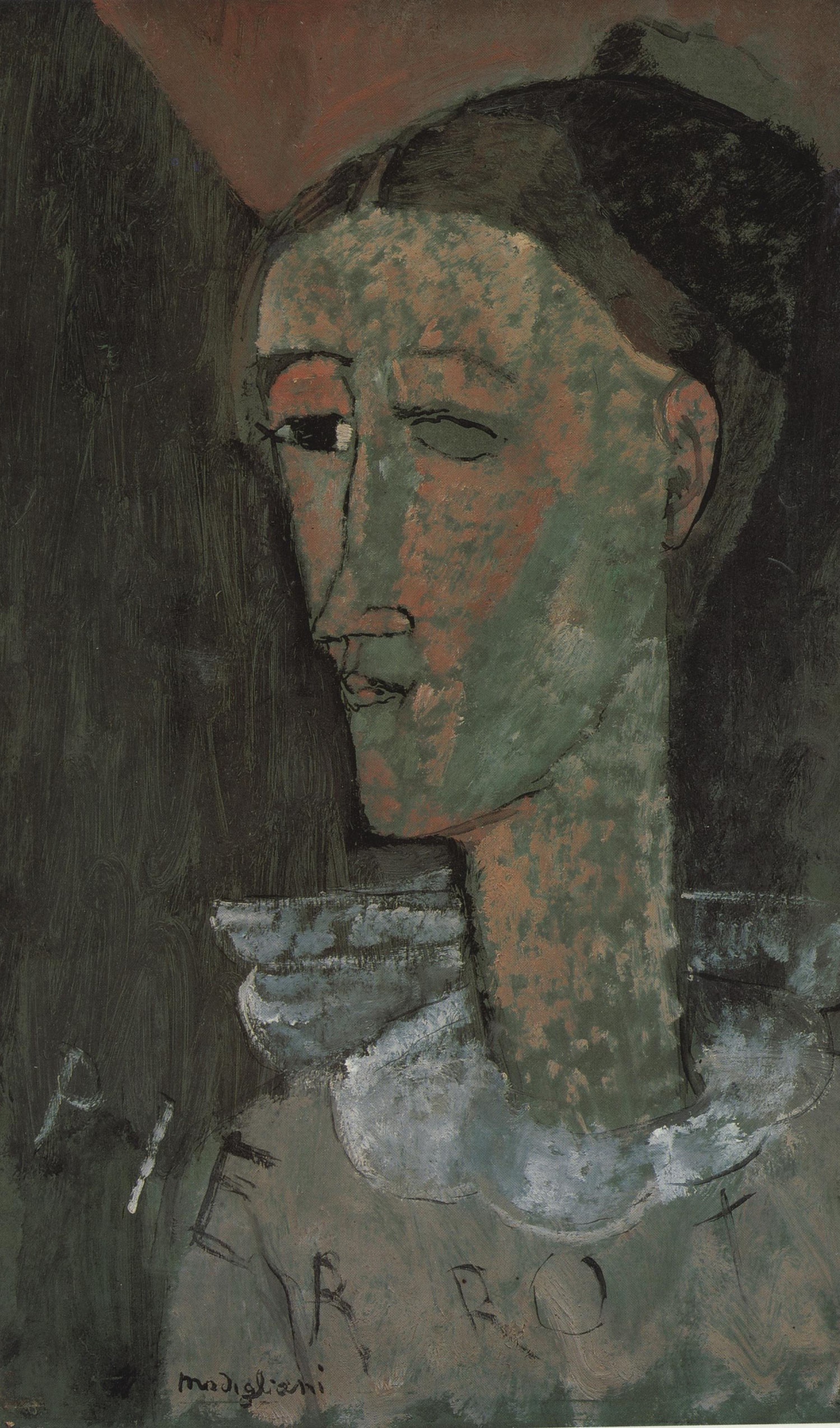

Once realized, Modigliani’s vision was to remain essentially unchanged. His sublime Pierrot with Ruff of about 1911, in spirit a self-portrait, communes with his 1915 painted self-portrait as Pierrot and, still later, “becomes” the face of the great self-portrait painted in the last year of his life. The Pierrot’s knowing gaze, gently smiling mouth, distinctive eyebrows, and oval face bear an uncanny resemblance to Spinoza’s portrait, which Modigliani may have seen in reproduction.[xiii]

Left to right: Pierrot with Ruff, c.1911; Portrait of Baruch de Spinozza, c.1665; Self-Portrait as Pierrot, 1915; Self-Portrait, 1919

It is often claimed that Modigliani wanted to devote his career to carving in stone and that his delicate health prevented this. But sculpture alone would never have given complete fulfilment to an artist so in love with drawing and painting and so able, through both, to convey the subtlest nuance of character and mood. Modigliani was utterly entranced by his fellow beings and dedicated his art to their inner beauty and richness of character. His deep psychological insight was described by the Russian artist Léopold Survage, whom he painted in 1918:

He read the character of someone near him very accurately and swiftly. This psychological gift was such that you could say his sitters resembled their portraits rather than vice versa. He underlined and exaggerated the characteristics of his sitters and brought out what was hidden by secondary and subsidiary features. . . . It was human beings that interested him and the invisible forces that were at work in them. Behind the physical appearance he imagined a mysterious world.[xiv]

The public perception of Modigliani remains predominantly that of a wild, debauched, drug-addled bohemian. Yet, from his earliest works to those made at the very end of his life, there is not the slightest evidence of their having emanated from the hand of a dissolute inebriate. Each line, brush mark, and patch of color, however slight, makes an essential contribution to the energy, harmony, and inner calm of the composition. Whatever Modigliani’s excesses, they are absent from a unique visual poetry of enduring beauty and humanity.

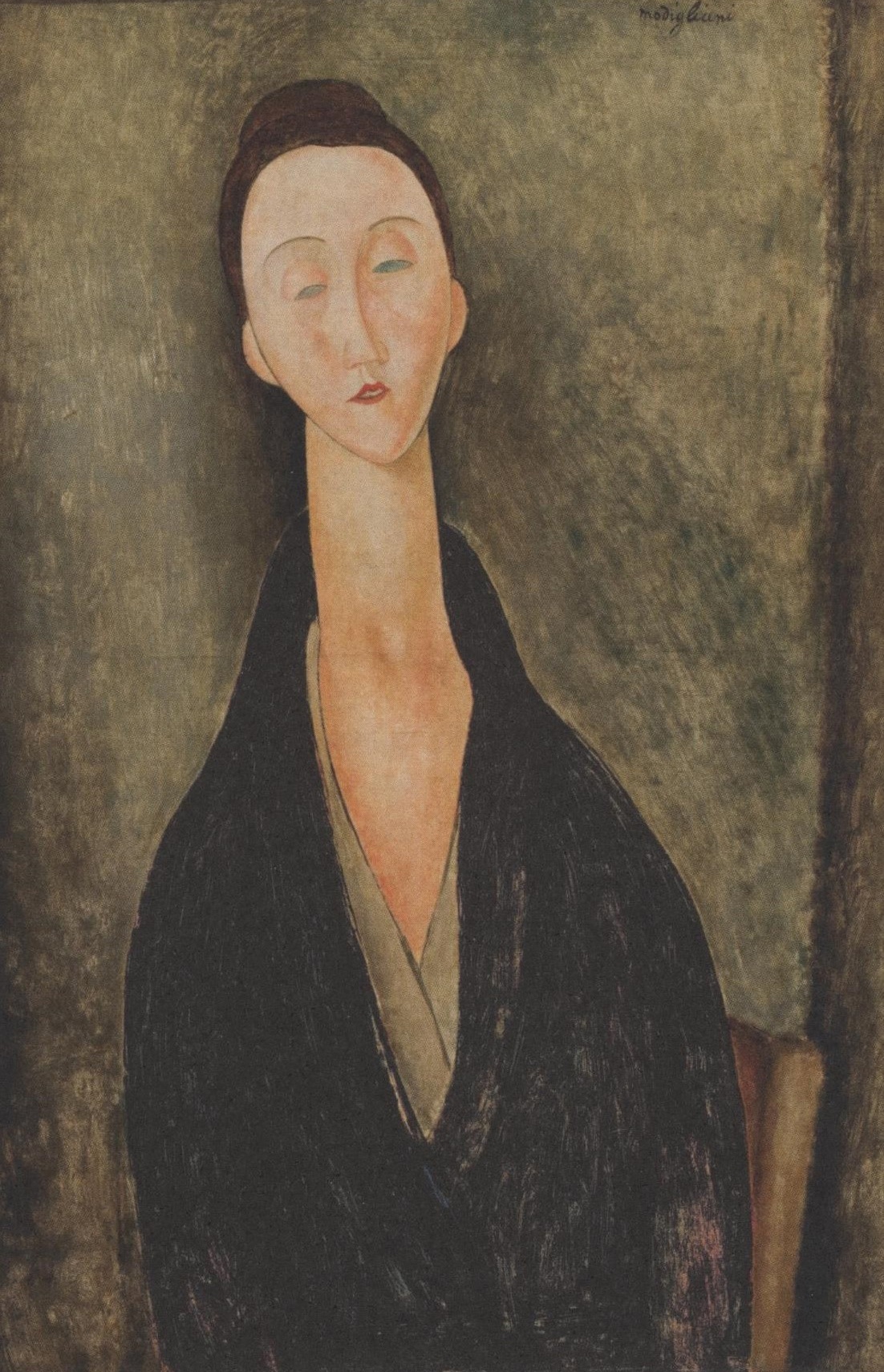

Lunia Czechowska, who sat for one of Modigliani’s last portraits, recounts a moving incident, not long before he died: “While I was preparing dinner, he asked me to lift my head for a few moments and by the light of a candle, he drew a beautiful sketch on which he wrote”:[xv]

Life is a gift

From the few to the many,

From those who know and who have

To those who do not know and do not have.

Lunia Czechowska, 1919

Epigraph: Quoted in Noël Alexandre, The Unknown Modigliani (New York: Harry N. Abrams/Fonds Mercator, 1993), p. 90.

[i] For the delirium and nightmares, see Alexandre, The Unknown Modigliani, p. 29.

[ii] Quoted in Ambrogio Ceroni, Amedeo Modigliani, peintre (Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1958) p. 17. Translated from the French by the author.

[iii] Quoted in Alexandre, The Unknown Modigliani, p. 89.

[iv] After his excommunication from the Jewish community in Amsterdam, Spinoza called himself Benedictus de Spinoza and signed his correspondence accordingly. For Einstein, see Walter Isaacson, Einstein: His Life and Universe (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007), pp. 388–89.

[v] For Spinoza’s drawings (or “Draughts”), see John Colerus, “The Life of Benedict de Spinosa” (1706), appendix to Frederick Pollock, Spinoza: His Life and Philosophy (London: C. Kegan Paul and Co., 1880), pp. 417–18.

[vi] Gustave Coquiot, “Modigliani,” in Des peintres maudits (Paris: A. Delpeuch, 1924), pp. 103–4. Quoted in English in Modigliani: The Inner Eye, exh. cat., Lille métropole musée d’art moderne, d’art contemporain et d’art brut (Paris: Gallimard, 2016), p. 107.

[vii] For Jean Alexandre’s letters, see Alexandre, The Unknown Modigliani, pp. 75–82.

[viii] The Cellist is reproduced in Alexandre, The Unknown Modigliani, p. 64.

[ix] Anna Akhmatova, Memoir on Modigliani,included in her Pages from a Diary 1958–1965. [RN: we are still trying to track down Poem without a Hero for citation]

[x] Citation TK.

[xi] Citation TK.

[xii] “Happiness is an angel”: Quoted in Alexandre, The Unknown Modigliani,p. 109.

[xiii] The self-portrait of 1919 is in the collection of the Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo.

[xiv] Quoted in Werner Schmalenbach, Modigliani: Paintings, Sculptures, Drawings, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel, 1990), p. 202. Modigliani’s portrait of Survage is in the collection of the Ateneum, Helsinki.

[xv] Quoted in Alexandre, The Unknown Modigliani, p. 89.