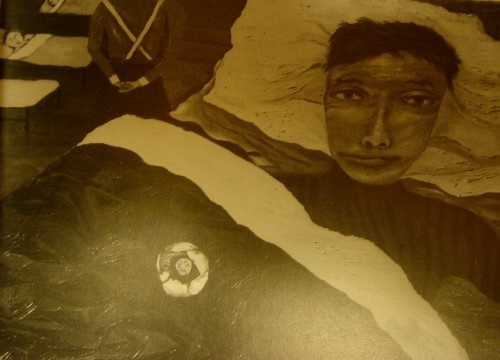

Freud was seventeen when he painted this autobiographical work. The haunting, haunted mask-face with its single Cyclops eye against the backdrop of frightened horses and smoulderingly beautiful colours portray a nightmarish scene of dream-like nostalgia and sadness present in no other Freud painting. It touches directly upon his 'Exodus' from Germany. War. The Nazi Jewish persecution. And his adored grandfather Sigmund.

Leigh Bowery:

Do you think very much about being Jewish? ……...

Lucian Freud:

I never think about it. Yet it's a part of me - linked to my luck. Hitler's attitude to the Jews persuaded my father to bring us here to London, the place I prefer to anywhere I've been.

In conversation with Robert Hughes:

My work is purely autobiographical. It is about myself and my surroundings. It is an attempt at a record.

And John Russell:

As a young man, I could never put anything into a picture that wasn't actually there in front of me. That would have been a pointless lie, a mere bit of artfulness.

Freud grew up in Berlin. Under growing Nazi power, he remembers being watched all the time by his parents and governesses; being escorted to and from school; and the menacing presence

of the Brown shirt gangs. Also a Jewish cousin being beaten up.

In 1933, Hitler became chancellor. Freud witnessed the burning of the Reichstag and increasing Jewish repression. His mother forbade him to draw swastikas, a favourite symbol among his school friends. When he asked why Jews were better than anyone else, she replied 'Because they don't kill other people'. Being Jewish, he was barred from the Hitler Youth. Freud remembers seeing Hitler 'He had huge people on either side of him. He was tiny'.

This searing childhood experience contributed to his adult obsession with solitude. 'All the real pleasures were solitary. I hate being watched at work. I can't even read when others are about.'

In 1937, Freud visited his grandfather in Vienna, and saw the ever-greater danger to Jews.

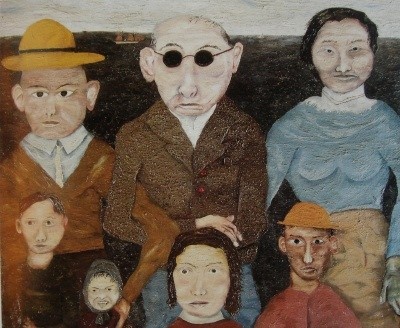

The Refugees 1941, [above] - the central figure being the Jewish family dentist - appear traumatised [except for the little girl defiantly sticking out her tongue], perhaps awaiting interrogation, as had his grandfather under the Gestapo.

It was on his maternal grandfather's estate, in northern Germany, that Freud acquired his life-long love of horses. And in painting the restlessly moving horses that appear in this and no other painting, Freud must also have relived his most vivid childhood memory - his grandfather's horses 'plunging and whinnying' in panic as the stables burnt down.

Upon arriving in England in 1933, at the age of eleven, Freud was enrolled at Dartington Hall. Avoiding the classes of a detested art teacher, he learnt to ride 'I used to ride all day and got further and further behind'. He even considered becoming a jockey. Horse-drawn carriages were still common in London. And he remembers being concerned at how harshly the horses were often treated.

He was fifteen when he carved his only horse sculpture [below] which his father showed to

The CentralSchool of Arts and Crafts in Holborn. He was given a place but, rebelling against the academic teaching, he would visit the Dominion Cinema in St Giles Circus, watching 'anything with horses in it' - particularly westerns.

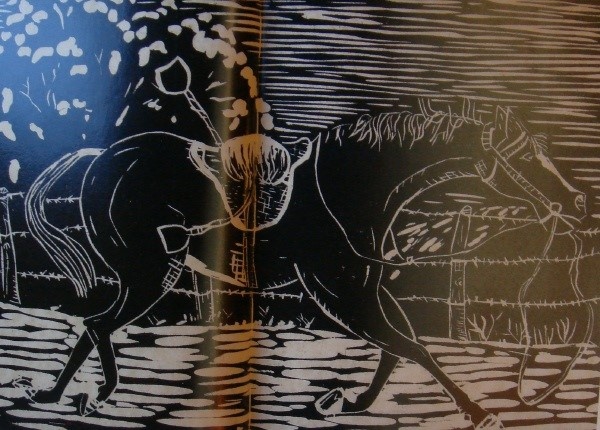

The horse below, its rider jettisoned, is racing for freedom - its fear accentuated by the angle

of 'flying' stirrups, the barbed-wire and 'speed lines' gouged into ground and sky. This print and Runaway Man, also of 1936, are filled with the urgent movement of escape evident in no other painting, save this.

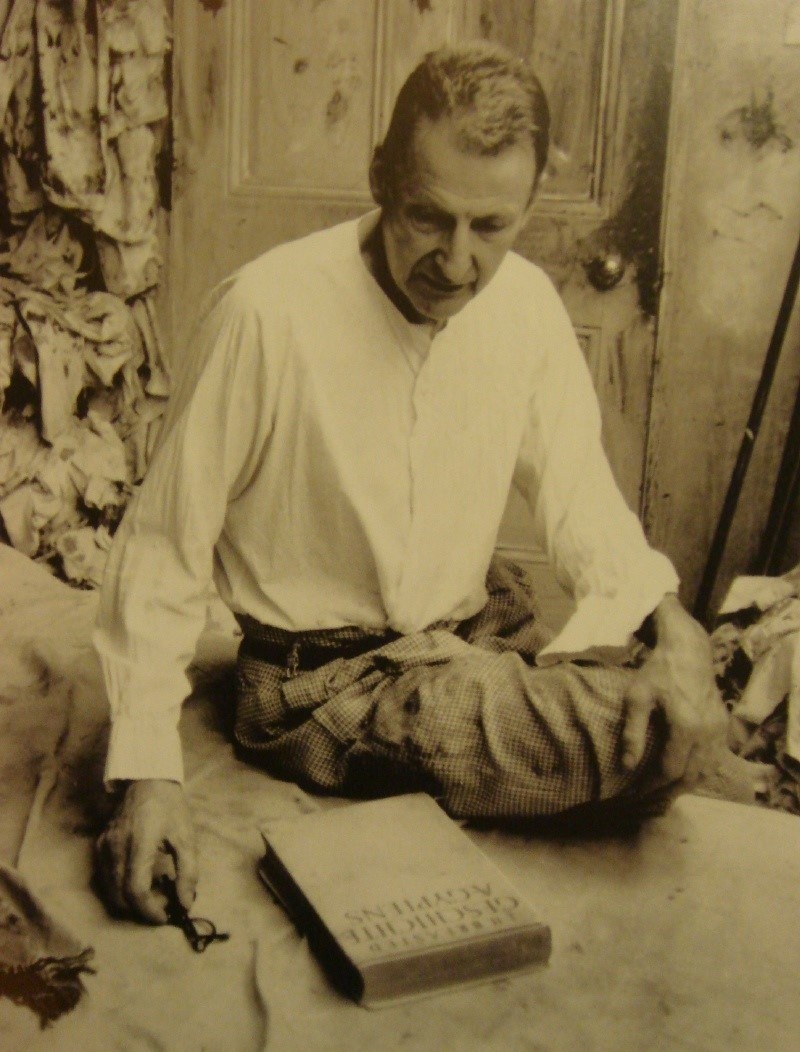

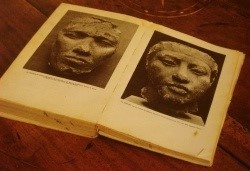

In 1939, Freud was given J.H. Breasted's 1936 book Geschichte Aegyptens. Its abiding effect is apparent in this painting and other early works; and in the two paintings [one reproduced page 6] and etching [see P.6]done in the nineties, featuring the two illustrated heads below that, over sixty years, have most moved him. Julia Auerbach's c.1989 photograph [left] of Freud contemplating the book, communicates its singular place in his thinking.

William Feaver, a foremost authority on Freud, and curator of the 2002 Tate Freud retrospective, in his exhibition catalogue, places considerable emphasis on the book's importance to Freud and his obsession with and belief in the living reality of the reproduced mask-faces unearthed from the court of the enlightened pharaoh Akhenaten. Also on his deep affinity with Akhenaten.

And on Sigmund's last book Moses and Monotheism, with its themes of Akhenaten's influence on Moses, an Egyptian and 'The Exodus':

'Freud's pillow-book, his painter's companion - his bible it could almost be said - for sixty years.The book could be Freud's special patient. Much handled, spine broken, it falls open at plates 120-1: two plaster faces with pre-occupied eyes and bashed noses unearthed at El-Amarna shortly before the First World War in what was identified as the workshop of Thutmose, chief sculptor to Akhenaten.

Who were they? More to the point: who are they? The one on the left - 'Head of a Man' - could be Amenhotep 111, whose son, Amenhotep 1V [1372-1358 BC] was reckoned by Breasted [the book's author] to be 'the most remarkable of all the Pharaohs and the first individual in human history'. Amenhotep 1V renamed himself Akhenaten after Aten, the sun god, whose cult he created and at whose prompting he closed down Thebes and established El-Amarna, the capital of civilisation that lasted twelve years.

Long-nosed, thin-lipped, Akhenaten certainly looked more individual than any of his predecessors. A monotheist and poet, he commissioned images of himself seen - as no pharaoh had been seen before - dandling his children and treating his wife Nefertiti as an equal. It is her painted bust in the Amarna room in the EgyptianMuseum in Berlin that has served to place her on every list of the world's most beautiful women ever. Akhenaten's innovations, an insistence on naturalism in art among them, provoked reaction: after a brief reign of his young son-in-law Tutankhamun, polytheism and high formality resumed. The names Aten, Akhenaten and Nefertiti were chiselled off palace walls and El-Amarna crumbled into oblivion.

The style and individuality of the heretical Pharaoh make him [Freud] sympathetic.

I read about him. The terrific loneliness of the king. Not many monotheists around: all these little gods and then one god only. [Lucian Freud]

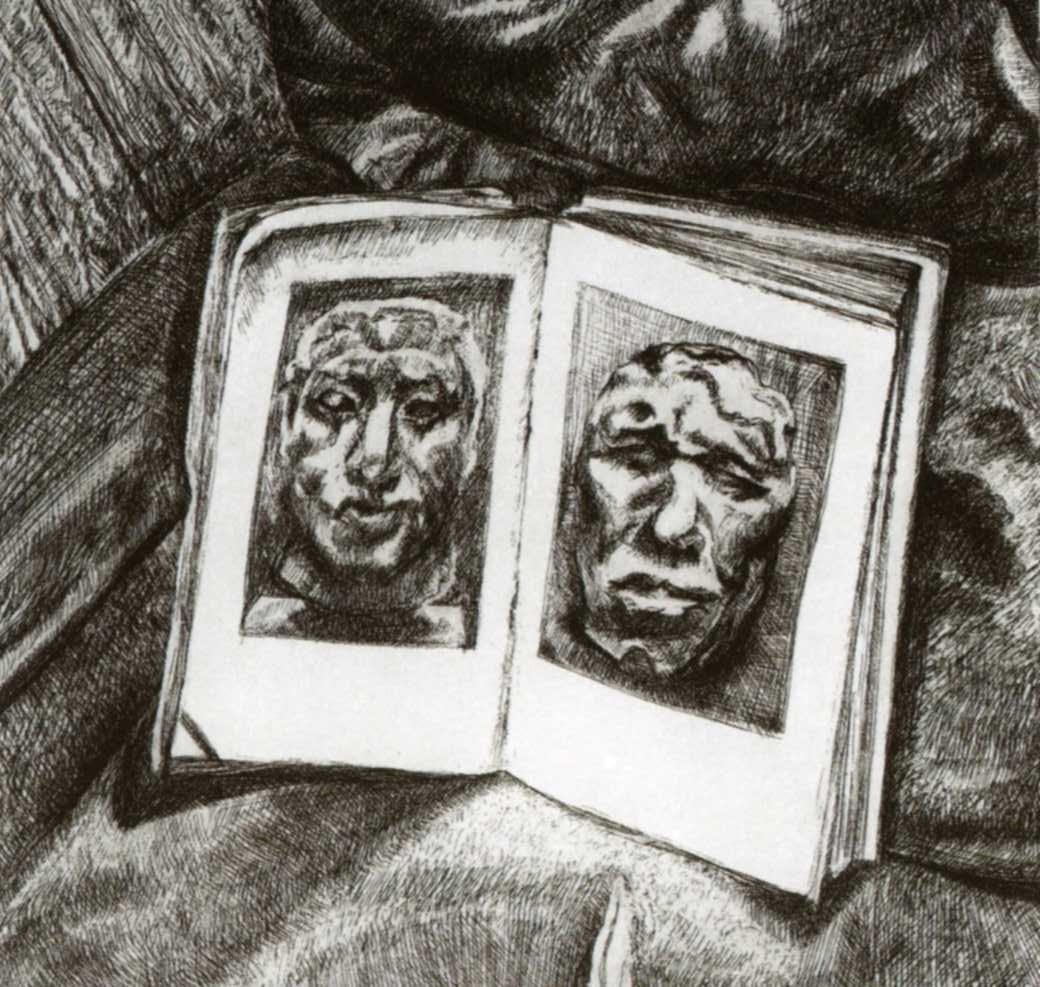

Equally moving, the ancient faces reproduced in Plates 120 and 121 of Geschichte Aegyptens, the brownish gravures softening the dark of their eyes, are no less vivid and poignant for being the faces of persons unknown. Indeed, identification would be a distraction. Freud has used them twice in paintings [Still Life with Book 1991-2 and 1993. And in an etching 'The Egyptian Book' 1994].

By painting them I didn't go very far afield. I thought about those people a lot. There's nothing like them: they're human before Egyptian in a way. When you find things very moving, the desire to find out more lessens rather. Rather like when in love with someone, you don't want to meet the parents.

Freud was given Geschichte Aegyptens soon after he began at the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing in June 1939. Co-incidentally in March that year, nine months after arriving in London and six months before his death, Sigmund Freud published Moses and Monotheism, describing it as 'quite a worthy exit'. In it he suggested that an official called Tuthmose [not the sculptor] at the court of Akhenaten was Moses who led the Jews out of Egypt, the Exodus being 'like a true trauma in the history of a neurotic individual' and Moses, like Akhenaten, an intermediary between the one and only God and the chosen people.

My grandfather didn't endear himself to the Jews by suggesting that Moses was an Egyptian,

an Egyptian floating down the river. An outrageous book: his final kick at the Talmud.

'Memory-trace'- Sigmund Freud's term - lingers in myth, distinct yet imprecise, like an after-image on the retina. Whether seen in reproduction, or in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, the

El-Amarna 'portrait masks' are substantial objects, true images, not apparitions from three millennia ago. They are whoever they are, irrespective of context, not mere relics or illustrations. Anonymity dignifies them. They are in Lucian Freud's phrase, 'an intensification of reality'.

He often says, 'I don't want mystification.

William Feaver 2002

William Feaver, in his major 2007 monograph on Freud, again focuses on the book's importance - in particular the role of the two mask-faces in many of his portrait heads:

'Novelty was unnecessary and fantastical elaboration uncalled for in the light of what became for Freud an immediate and lasting influence, a sort of sacred form book: J.H. Breasted's Geschichte Aegyptens…. He would look through it, ranging across the art of Ancient Egypt, pausing at some sculpture [basalt dogs and falcons], the Faiyum encaustic portraits that once adorned mummies [his grandfather had owned a few] and the crowned heads, especially that of Nefertiti, Queen of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, where his maternal grandmother used to take him on winter afternoons. Much consulted over the years, the book now falls open straight away at Plates 120 and 121: photographs of two stoical plaster faces dug up from the site of a sculptor's workshop at El-Amarna and dated c.1360 BC, the reign of Akhenaten, the first Pharaoh, and quite possibly the first person in history, to have himself represented as he actually looked. The two men's faces are individual too, poignantly so. To Freud they are all the better for not being identified by name or status…..Freud used Geschichte Aegyptens as a resource right away [there are hints of Plate 121 in his 1939 Self Portrait] and went on doing so until, in the early Nineties, he made it a subject in itself, Still Life with Book, 1993, resting it against a cushion, open at the favourite pages. Like ghost templates the photogravure reproductions of the faces from El-Amarna are at the back of the minds, as it were, of many of his portrait heads, particularly those of men……..'

Mask-Heads [frontispiece of William Feaver's monograph]

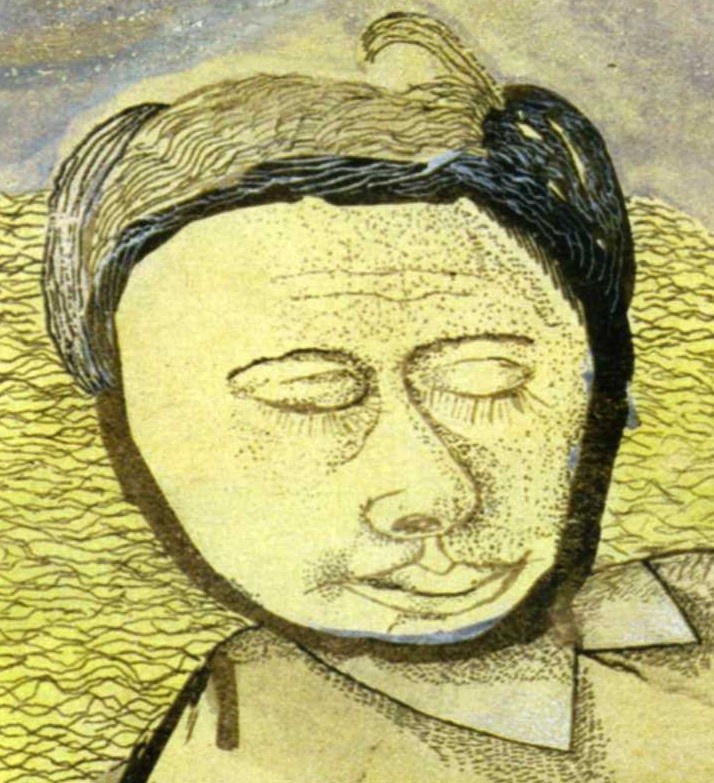

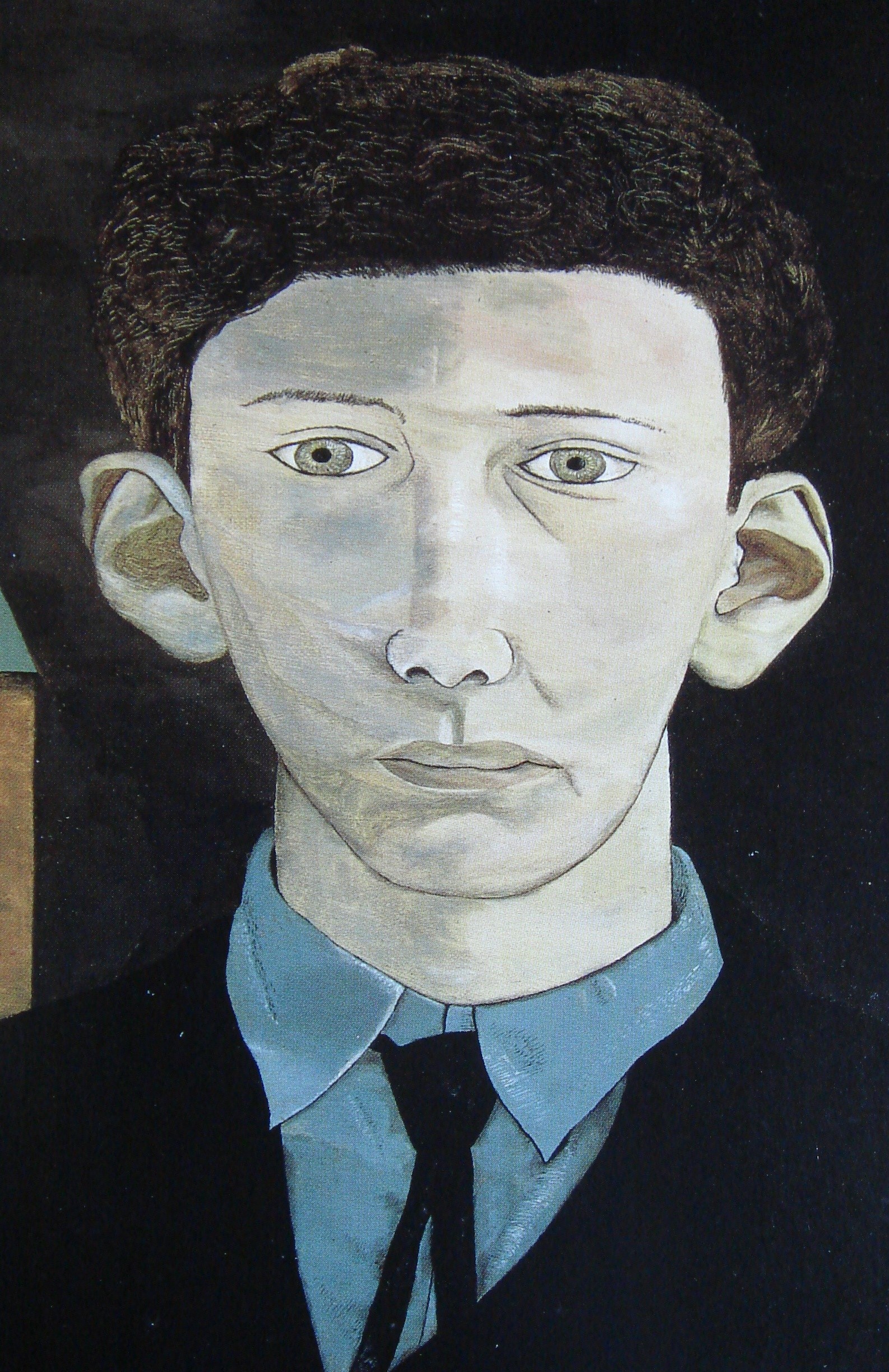

The following four self-portraits [all details from larger compositions] were painted between 1940 and 1943. As with the head in this painting, each is influenced by the two mask-headsreproduced in Geschichte Aegyptens.

From 'In The Silo Tower' 1940

From 'Landscape with Birds' 1940

From 'Hospital Ward' 1941

From 'Man with a Feather' 1943

Sigmund Freud

Freud's father Ernst, an architect, was the younger of Sigmund Freud's two sons. Sigmund would visit Berlin for cancer treatment and encourage Lucian in his drawing. He remembers him being 'marvellously understanding and amused' about his vocation and giving him The Arabian Nights illustrated by Edmund Dulac, a family friend; also the prints of Breughel's Seasons.

He felt much closer to him than to his own father.

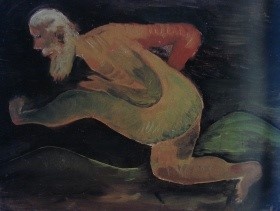

Runaway Man [detail] 1936

Runaway Man whilst reflecting Freud's love of limericks - particularly those of Edward Lear - is Freud's only painting of a man seemingly running for his life. Given its date, close facial resemblance to Sigmund, and fear, apparent in the expression and physical tension, it is as though Lucian is willing his grandfather to escape in all haste from life-threatening danger.

Robert Hughes, in his book on Lucian Freud, writes of Sigmund:

'Though harried by the Gestapo and tormented by cancer of the mouth he was able to ship

his collections of books and papers to London where he settled in Hampstead.'

William Feaver:

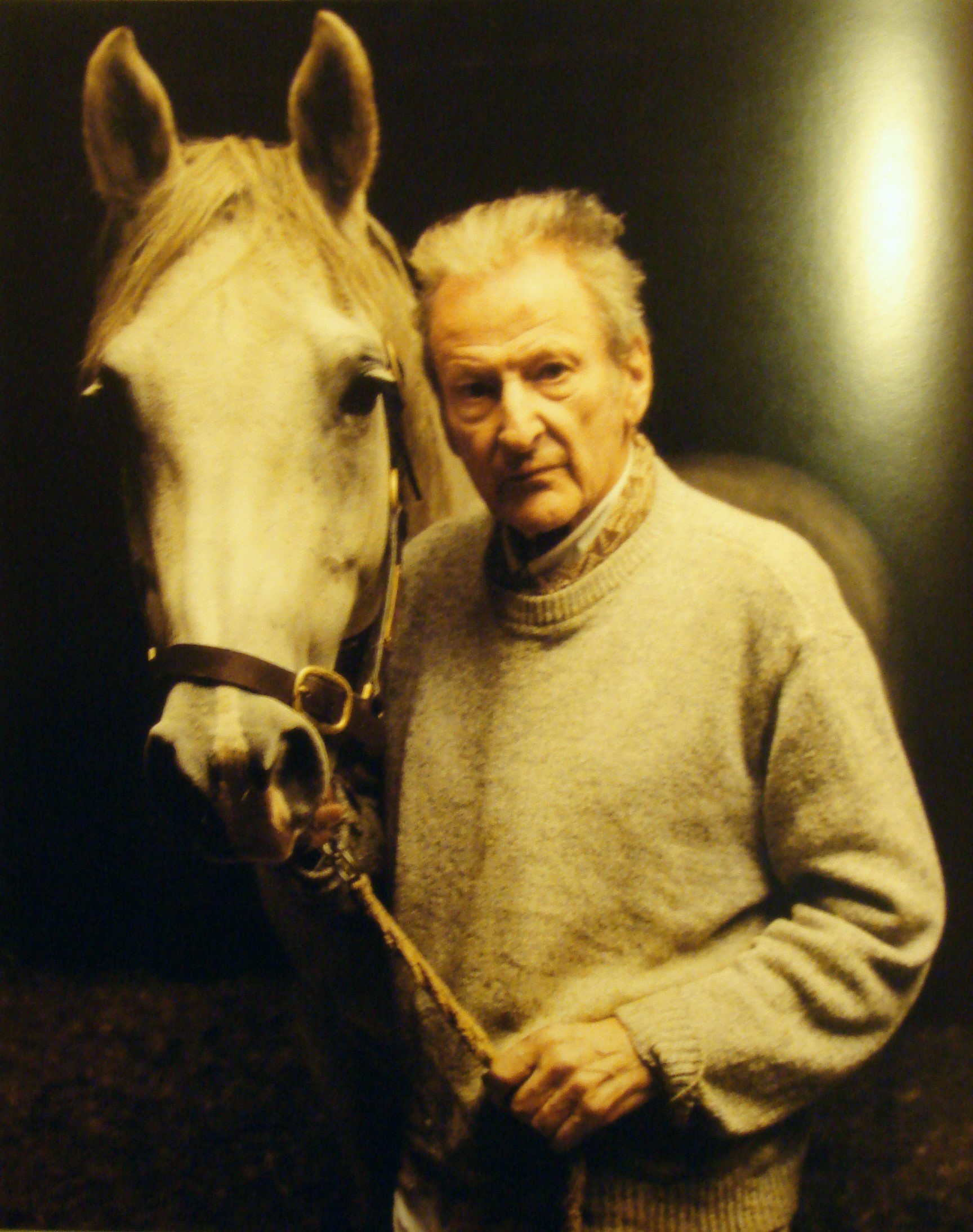

'On Saturday 25th June 1938, Lucian and his older brother Stephen went to see their grandfather, who had just arrived from Vienna three weeks before. Setting aside Moses and Monotheism, he showed them round the garden at 39 Elsworthy Road, where he lived that summer before moving into 20 Maresfield Gardens and surrounding himself with his cherished Greek and Egyptian antiquities. Lucian and his brother Stephen were filmed with their grandfather examining the goldfish.'

Sigmund Freud was London's most famous Jewish refugee. Lucian was very proud of him; and affected by his charismatic personality, his immense learning so lightly worn, his courage and humour - also his encouragement of Lucian's artistic gifts.

Sigmund's death, in the year this was painted, was, for him, significant. Lucian:

There was a sort of hole in his cheek like a brown apple: that was why there was no death mask made, I imagine. I was upset.

And:

I've read certain things. I've read the case histories he did with Breuer. And there's a volume called 'Humour and Mania', I went through that looking for jokes and there were lots of really good ones. [He] was extremely nice to me. I did a bit of sculpture at school, a small alabaster fish lying on a rock and I thought it was rather good and gave it to him and he seemed to like it. He had a collection of antique sculpture. Marie Bonaparte was with him and he gave her my fish saying 'I'm sure you won't mind my giving it to Princess Marie because when you become an artist she will be your first patron.'

He seemed fairly youthful, even in London; he had such humour and wisdom, very light-hearted really…..the thing is my grandfather was a very cultivated man; he seemed marvellously understanding and amused. I think that the more deeply cultivated you are the stronger position you are in to deal [with] and understand the things which, on the face of it, might well be abhorrent to you, and things which might engender fear and disgust and even hate. My grandfather was forced into neurology; he wanted to be a surgeon but anti-Semitism had closed those ranks and surgeons had already established themselves to the point where they kept Jews out. This science which he invented was, after all, to do with extreme cases. There was no idea that this could be used to pass the afternoon of somebody who could no longer find anyone else to bore.

From William Feaver, Lucian Freud, 2007

In London, Sigmund Freud wrote:

In the certainty that I should now be persecuted not only for my line of thought but also for my 'race', I left the city which, from my earliest childhood, had been my home for seventy-eight years.

Uprooted and suffering from worsening cancer, he nevertheless felt compelled to revise and conclude his book on Moses, in which he stated:

The great religious idea for which the man Moses stood was, in our view, not his own property: he had taken it over from King Akhenaten.

These ideas and ancient links with Lucian's own exodus seem expressed through the almost hypnotically adapted Egyptian mask-head that so obsessed him? Is this painting also a memorial to his revered and loved grandfather?

The arching, rhythmic curved shapes of the horses recall those painted by Franz Marc whose work Freud knew. Yet in contemplating Freud's restless, wreathing horses and the uppermost horse's missing teeth, flared nostril and opened-eyed terror, it is Picasso's dying Guernica horse that comes most forcefully to mind. Freud felt strongly about the Spanish Civil War and took its cause to heart.

In 1938, Freud's paintings were included in a children's exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim's Gallery in Cork Street where Roland Penrose, the artist, collector and friend of Freud's, ran

The London Gallery. Penrose knew Picasso and collected his work. When he entrusted Freud with his Weeping Woman of 1937 for an exhibition in Brighton, Freud spent the entire train journey studying it:

I was so amazed that the bright sunlight in no way made it any worse or more garish or weaker or more painty. It was as powerful and strong as possible. You can use your intent to make anything seem like anything: Picasso's a master in being able to make a face feel like a foot.

Picasso's studies for Guernica were shown in October 1938 at the New Burlington Galleries,

a stone's throw from Cork Street; and then with Guernica at the Whitechapel Art Gallery [December 1938 to mid January 1939]. The exhibition was opened by Clement Attlee,

Labour party leader; and each evening talking films were screened on the Spanish Civil War. Over 15000 people visited in the first week - the price of admission being a pair of boots in fit state for sending to the Spanish front. Both showings, arranged largely through Roland Penrose, honorary treasurer of the National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief, raised funds for the Spanish war relief. Given Freud's passionate concern for this cause and admiration for Picasso, [also his friendship with Penrose] he would have seen both exhibitions. His anguished horse's head is a symbol of suffering; and tribute to Picasso.

A further intriguing influence suggests itself. Sigmund Freud, with his love of ancient Greece, would almost certainly have spoken to Lucian about Odysseus's escape from the Cyclops's cave [as a child he would also have heard it from his mother, a classicist], perhaps inspiring the sheepskin-clad Cyclops-eyed figure, with its possible reference to Odysseus's 'Exodus' and his own.

Conclusion

Subtle richness and variation of colour, tone and texture; undulating rhythms of line and form come together in a wonderfully controlled, harmonious way to create a complex, poignant work of mysterious power and beauty.

Childhood memories, Freud's escape from Jewish persecution and likely death - reflected

in the wistfully expressive mask-face. Panicking horses. Freud's love and veneration for his grandfather; and regret that no death-mask of him existed. An abiding obsession with

Geschichte Aegyptens and its 'living' mask-faces from the court of Akhenaten - the enlightened monotheistic pharaoh with whom he felt such empathy. Sigmund's claim that Moses, an Egyptian, had taken his teaching from Akhenaten. The link between Moses leading the Israelites from Egypt and Lucian's own exodus. Sigmund's death and the publication of Moses and Monotheism in the year 'Portrait with Horses' was painted.

All are interweaving elements in this unique, very moving image of deep symbolic, psychological and artistic importance in Freud's maturing vision.