'I am at Ryde on the Isle of Wight, and as soon as my canvases arrive I will begin work' wrote Sisley to his dealer, Durand-Ruel, one hundred years ago this month. His painting materials failed to arrive, and his meagre finances prevented the purchase of any, resulting in just a few drawings which record this, his second of four sojourns in England - the only country Sisley was to visit outside France.

Today, despite his reputation, Sisley remains for most an unknown figure, echoing the gently pulsating light which moves elusively through so many of his paintings. Van Gogh called him the gentlest of the Impressionists. And he stands with Monet, Pissarro and Renoir in the hierarchy of a movement dedicated to painting the vibrancy of light and colour. But, unlike his three friends, Sisley died in poverty, unrecognized and an Englishman.

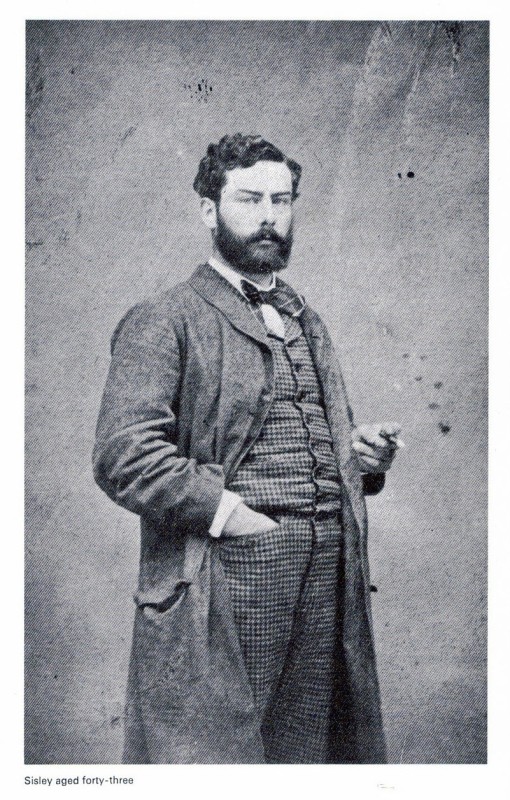

Sisley was born in Paris of English parents in 1839. His great grandfather had been a smuggler from the Romney Marshes, whose trade with France had established there a prosperous and respectable family business. From his mother Sisley inherited a love of music and literature. He enjoyed a comfortable French upbringing, but it was his English ancestry which determined, to a remarkable degree, his character and his art.

At the age of eighteen, Sisley arrived in London to study commerce before entering the family business, then principally involved in the sale of artificial flowers to South America. In keeping with his quiet and reserved nature, no word or sketch documents the process of Sisley's self-discovery. It is known only that museum visits took precedence over business study and that he greatly admired Constable, Turner and Bonington. At the National Gallery Sisley would have seen Hobbema's Avenue at Middelharnis. Its serenity, space and light, its inate construction and order are elements characterizing Sisley's finest painting. And the symbolic pathway leads the eye through his life's work.

There exist certain similarly painted early works, some of the same motif, by Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and Sisley, made when they were painting together and united by a common ideal. But if one considers Monet's exuberant embrace of atmosphere, Pissarro's rugged humanism and Renoir's lyrical caress, then each is the mark of a very different temperament.

Sisley was the only Impressionist to devote himself almost wholly to landscape. And his character is mirrored in the meditative quality of his painting. Curiously, of all the Impressionists' work, it is his alone which can suddenly and vividly be evoked by an autumn or spring day in Hyde Park. His particular temperament and feeling for the English landscape painters, his decision made in England to become a painter and his subsequent visits all underline a deep link with his ancestral land. London provided the catalyst and the turning point for Sisley-as later, though in very different circumstances, it was to do for Van Gogh. Upon his return to Paris in 1862, Sisley, assured of family support, entered the studio of Gleyre, a kindly academic painter. There he met Monet and Renoir who became his life-long friends. Sisley's first recorded landscape,painted in 1865, of the forest Celle-Saint-Cloud is a very serious work, and remarkable in its authority and size. There are discernible influences, among them Corot and Courbet, but it is the genesis of Sisley's gift. The Southampton painting of 1867 (see illustration, no. 1) depicting the same forest is more freely handled.

Sisley married in 1866 and Renoir described his wife as having a very sensitive nature and being exceedingly well-bred. She remained Sisley's devoted companion and supporter and Renoir's wonderful painting of them in 1868, after the birth of their son and daughter, is a moving portrait of a tender and lasting union. Sisley's comfortable circumstances may partly explain the existence of only eighteen known paintings before 1871. The 1870 Franco-Prussian war caused his father's ruin and death. Sisley was forced to turn completely to his painting for a livelihood. He moved to the village of Louveciennes (see illustration, no. 10), fifteen miles west of Paris. A life-long struggle had begun which was to deny him even the ownership of a home.

Sisley participated in the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874. Later that year he spent four months in England and painted his wonderful Hampton Court series -

also his only view of London (see illustration, no. 6). The work of the 70s radiates a joyous vibrancy and purity of tone. It is Sisley's awakening, but its optimism and burgeoning force belie increasing financial hardship. Few paintings sold and much of Sisley's correspondence is a humiliating request for help.

In 1879, whilst preparing for the official Salon exhibition in the hope of gaining some recognition, Sisley was evicted from his home. In desperation he turned to his patron, Georges Charpentier, the publisher of Zola.

28th March, 1879

My Dear Monsieur Charpentier,

After all the proofs of sympathy that you have given me, it is no secret I betray in explaining my unfortunate position. Since I decided to exhibit at the Salon I find myself more isolated than ever. You are my only hope.

I am forced to leave Sevres and without resources. I do not know where to turn. I need 600 francs. But as it is rather a large sum I only ask you to advance me half of it. A week from today I may be able to find the rest. Perhaps among your friends there may be someone who, to do me a kindness, would advance me the sum in return for something of mine.

If I am hung, the Salon will help. I hope I shall be. In any case you will have con-tributed to getting me out of the most disastrous position in which I have yet found myself. I shall be very grateful. I should like to see you one of these days.

Meanwhile I shake your hand.

The Salon rejected Sisley's entry, but Charpentier's immediate assistance enabled him to move to an apartment. A further move brought him to the surroundings of Moret-sur-Loing, fifteen miles south west of Fontainebleau. Sisley fell in love with the peace and beauty of the place, and remained there until his death. He began painting the same views at different hours and seasons, and so enthralled was he with the countryside that he wrote to Monet urging him to settle there.

Sisley's inherent gaiety and his love of music give a particular sensitivity and lyricism to his work. One piece which especially inspired him was the trio from the scherzo in Beethoven's septet. 'It was this gay, singing phrase which captivated me' he told a friend. 'It called forth a response in me from the very beginning and I sing it continually, humming to myself as I work'. The only written record we have of Sisley's artistic beliefs is found in his correspondence with his friend, the collector and critic, Adolphe Tavernier: '... to give life to the work of art is certainly one of the most necessary tasks of the true artist. Everything must serve this end: form, colour, surface. The artist's impression is the life-giving factor.

Although the landscape painter must always be the master of his brush and his subject, the manner of painting must be capable of expressing the emotions of the artist. You see I am in favour of differing techniques within the same picture. This is not the general opinion at present, but I think I am right, especially when it is a question of light.

'The sunlight in softening the outlines of one part of a scene will exalt others and these effects of light which seem nearly material in a landscape ought to be interpreted in a material way on canvas.

Many of Sisley's paintings have areas lightly painted whilst others are painted in thick and brilliant colour. The effect created is one of changing light, movement, solidity and distance - of life.

There is a broader sweep to the work of the 80s, an added scale, a mellowing of tone and often melancholy-a sense of grandeur. Matinee de Novembre of 1881 (see illustration, no. 14) conveys this changing mood and underlines the dominant role of the sky in Sisley's landscape painting.

'The sky is not simply a background: its planes give depth (for the sky has planes as well as solid ground), and the shapes of clouds give movement to a picture. What is more beautiful indeed than the summer sky, with its wispy clouds idly floating across the blue ? What movement and grace! Don't you agree ? They are like waves on the sea; one is uplifted and carried away. But there is another aspect - the evening sky. Clouds grow thin, like furrowed fields, like eddies of water frozen in the air, and then they gradually fade away in the light of the setting sun. Solemnity and melancholy - a sad moment of departure which I find especially moving'.

In 1883, Durand-Ruel showed seventy of Sisley's paintings in his Paris gallery. There followed in London a mixed exhibition with eight of his paintings. However, Sisley's work remained virtually ignored and his financial situation increasingly precarious.

17th November 1885

Dear Monsieur Durand-Ruel,

I have received the 200 francs. This will pay a bill which falls due on the 20th of this month and a few small debts. But afterwards ? By the 21st I shall again be without a sou. However I must give something to my butcher and my grocer; to one I have paid nothing for six months and to the other nothing for a year. I also need some money for myself at the start of winter. There are certain things I must have, and I would like to think that I can depend upon a little calm in order to work.

I am completely in pieces. Tomorrow or afterwards I shall send you three canvases. It is the only finished work I have.

Cordially, A. Sisley

25th November 1885

Dear Monsieur Durand-Ruel,

You are better placed than I to know what will please the collectors. Therefore return to me the two canvases you think less saleable. I will replace them on my next trip. The situation here remains unchanged.

Your very devoted, A. Sisley

The work of the 1890s is frequently denigrated. Certain paintings have an almost forced cheerfulness, but there are masterpieces - among them the views of the Loing and the church at Moret (see illustrations, nos. 18 and 19). Unexpected criticism from the pen of Octave Mirbeau, a champion of the Impressionists, prompted a dignified and rare gesture of open defiance demonstrating Sisley's unshakable belief.

Moret 1st June 1892

Monsieur Mirbeau,

An article on the Salon that appeared in The Figaro on the 25th of last May, in which you devoted a few rather unfriendly lines to me, has been brought to my notice.

I have never replied to criticism made in good faith. I always, on the contrary, try to profit by it. But there the intention to do injury is so evident that you must allow me to defend myself.

You have made yourself a champion of a coterie which would be happy to see me in the dust. It will not have this pleasure, and you will gain nothing by your unjust and perfidious criticism.

There! Do you think I was right to reply?

Very sincerely yours, A. Sisley

Sisley continued to live and work in solitude. He was growing old and was increasingly afflicted with temporary paralysis of the face and with rheumatism - the result of long sittings in the open. He also began to suffer the first effects of a fatal throat cancer. In the face of illness and worldly failure his painting and the

beauty of his surroundings sustained him. His friend, the writer Gustave Geffroy, gave this moving account of Sisley during his last years:

'Sisley was already in delicate health when he invited me to make the easy journey to Moret. We were admirably entertained by Sisley, his wife and daughter in their home which was both bourgeois and rustic. There I became better acquainted with the master's paintings. I had admired his work at an exhibition in 1883.

Alas, many of those same paintings were still against the wall, piled in corners. The vogue for Sisley's work had not yet come as it was beginning to do for Monet. And it did not take long to sense the sadness that lay beneath his resigned outward appearance and lively conversation.

'That marvellous day, perfect in its ambience of welcome and friendship, has for me remained marked by this premonition of an ageing artist who sensed that during his lifetime, no ray of glory would shine upon his art. This impression is reinforced by the fact that no one present on that day is now alive - not even Mademoiselle Jeanne Sisley, then in the full bloom of youth and beauty. Yet everything was magnificent and harmonious. We spent the morning in the studio and after lunch everybody took charabancs to Moret, the banks of the Loing, and the forest of Fontainebleau where Sisley, acting as master of ceremonies, spoke with unforgettable charm.

I have never forgotten the splendour of the trees, the glades and rocks of which he spoke so poetically; nor indeed his account of the lives and troubles of the river folk whom he knew so well through his studious and reflective existence spent by the river banks and beneath the poplar trees'.

In February 1897, 146 of Sisley's paintings were shown in his retrospective exhibition at the Georges Petit Gallery. The exhibition was all but ignored, and not a painting sold. In May, Sisley was invited to England and in Wales he painted his only seascapes. These, with three views of his beloved river Loing, were ironically to be his last paintings. Upon his return in September, Sisley made a final unsuccessful attempt to gain French nationality.

On 8th October 1898, his wife died. He had nursed her for much of the year. 'Sisley' recalled Renoir 'was the soul of devotion, looking after her tirelessly, watching over her as she lay in her chair trying to rest'. Sisley's three letters to Dr. Viau describe his final anguish:

28th November 1898

I am better than I would have believed possible after the last haemorrhage, and although ridiculously thin my strength is gradually returning. I am using dressing of arsenate of soda. I have rinses, and massage with Ponds

extract and Eau-de-Cologne for my back and legs. It is doing me more good than I dared hope, so you see, my dear friend, that I am recovering little by little.

31st December 1898

I cannot fight any longer, my dear friend, I am at the end of my tether. I can hardly sit long enough in a chair for my bed to be made, and the swelling in my throat, neck and ears makes it impossible for me to move my head. I think it will not be long now. If you know a good doctor, though, who would not want more than 100 or 200 francs, I will see him. If you could tell me the date and time when he would come, I would send a cab to the station.

Affectionately, and very sadly, I bid you farewell...

13th January 1898

I am collapsing with pain and with a weakness which I no longer have the strength to fight.

That same week Sisley called for Monet to bid him farewell and to ask that he care for his two children.

On 22nd January, Pissarro wrote to his son, Lucien : 'I have heard that Sisley is desperately ill. He is a great painter and in my opinion, ranks among the masters. I have seen paintings done by him of the most unusual vision and beauty.'

On 29th January, Sisley died at home, in the shadow of the church he had painted so wonderfully.

Three months later, twenty-seven of his paintings were sold for 112,320 francs. And in 1900, L'Inondation a Port-Marly (now in the Louvre), which Sisley had sold for 180 francs, was auctioned for 43,000 francs.

There exist 940 known paintings by Sisley. Dr. Francois Daulte, the Sisley authority, records in his 1959 Catalogue Raisonné 18 paintings before 1871; 329 during the 1870s; 371 in the 80s; and 162 between 1890 and his death. These figures are analogous with Sisley's quiet beginning, his awakening, the heightened grandeur of the 80s and his gradual defiant subsidence. Seen as a whole, the work has the orchestration and nobility of a great symphony. Sisley's genius reveals itself gradually. One marvels at his inspired and subtle touch which can render almost imperceptibly the nuance of light, colour, movement and season. Within the small radius of his surroundings, Sisley created his world. A simple and grand vision of rural life and man's transient presence amid an ever-changing yet constant and all-embracing landscape.

Sisley's painting remains as vital and true today. And his human achievement seems especially remarkable. To spend a lifetime, without financial reward or recognition, in battle with the elements, to pay homage to the beauty of a fleeting moment, is in itself an act of faith and greatness. Through intense, passionate study and zen-like self-abstraction come the serenity and sense of infinity in Sisley's work.

Finally, Sisley's magic cannot be defined, but it is very precious in a tormented age, spiritually bereft and visually beset by lifeless trivia and ugliness. Perhaps a young artist will look afresh at this master and the timeless themes he made his own.

This Introduction was adapted by The Sunday Times magazine for a feature article published on Sisley.