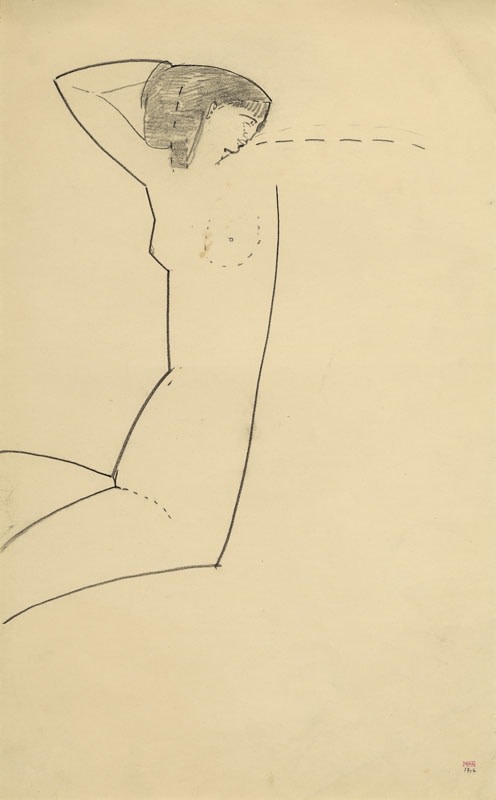

This rare and moving drawing portrays Anna Akhmatova both as ancient Egyptian goddess. And poet lost in her dream.

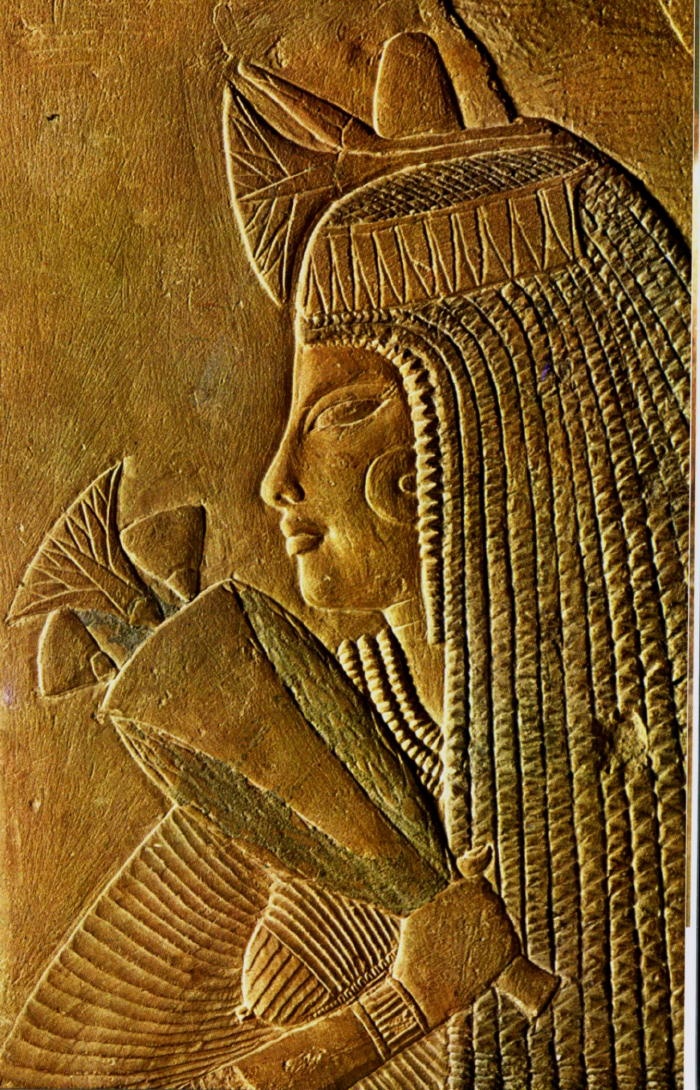

Erotic in its restraint and languid, sensual pose, it evokes the extenuated body and hair of Egyptian goddesses and queens portrayed in the sculptures and paintings which Modigliani and Akhmatova visited together at the Louvre during the summer of 1911.

Modigliani was captivated by Akhmatova’s extraordinary beauty, her nobility and statuesque presence which he saw mirrored in the women of ancient Egypt. And given his own poetic, mystical nature, he may even have imagined her, in a former existence, as an Egyptian queen.

Modigliani strove to purify his line, so he might convey the essential spirit of his subject. Of the three ‘Akhmatova’ drawings reproduced in The Unknown Modigliani [Nos. 91-93] this is the most simply drawn - without extraneous line or artefact to the extent even of the left arm being merely suggested; so that all attention rests upon the attitude of her head and revealing posture. So assured and expressive is the purity of line. And so perfect its placing upon the page, that it was probably the last to be drawn.

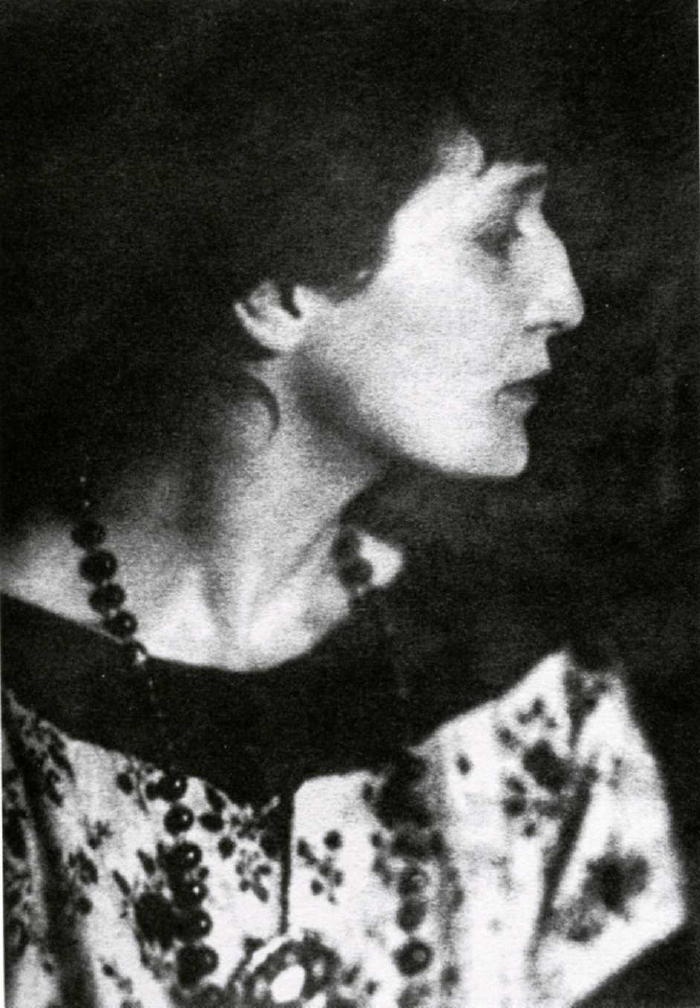

Anna Akhmatova

Anna Akhmatova [1889-1966] is considered, with Boris Pasternak and Osip Mandelstam, the greatest Russian poet of the twentieth century. She met Modigliani during her first visit to Paris, on honeymoon with her husband, in 1910. She returned alone in May 1911 and became very close to Modigliani. Theirs was a union of spirit derived from their shared passion for poetry.

Akhmatova records that Modigliani gave her some sixteen drawings he drew of her. All disappeared. In Memoir of Modigliani [1958 - 65] she recalls their love for each other:

‘In 1910 I saw him very rarely, just a few times. But he wrote to me during the whole winter. I remember some sentences from his letter. One was: Vous êtes en moi comme une hantise’ (you are obsessively part of me). He did not tell me that he was writing poems.

I know now that what most fascinated him about me was my ability to read other people’s thoughts, to dream other people’s dreams and a few other things of which everyone who knew me had long since been aware. He repeatedly said to me: ‘On communique..’ (we understand each other). And often: ‘il n’y a que vous pour réaliser cela.’ (Only you can make that happen).

We both probably failed to realise a crucial point: everything that was happening was for both of us but the prehistory of our lives – of his very short life, of my long life. Art had not yet ignited our passions, its all-consuming fire had not yet transformed us; it must have been the light and airy hour of dawn. But the future, which announces its coming long before it arrives, was knocking at the window. It lurked behind the lanterns, invaded our dreams and took on the frightening form of Baudelaire’s Paris which lay in wait somewhere in the vicinity. And Modigliani’s divine attributes were still veiled. He had the head of Antinoos, and in his eyes was a golden gleam – he was unlike anyone in the world. I shall never forget his voice. He lived in dire poverty, and I don’t know how he lived. He enjoyed no recognition whatsoever as a painter.

At that time (1911) he lived in the Impasse Falguière. He was so poor that in the Jardin du Luxembourg we sat on a bench and not, as was usual, on chairs since you had to pay for them. He complained neither about his poverty nor about the lack of recognition, both of which were clearly apparent. Just once in 1911 he said that the previous winter had been so tough for him that he had been unable to think even of that which was dearest to him.

He seemed to me to be encircled by a girdle of loneliness. I cannot recall him ever greeting anyone in the Jardin du Luxembourg or the Latin Quarter even though everyone knew everyone else there. I never heard him mention the name of an acquaintance, a friend or a fellow painter, and I never heard him joke. I never once saw him drunk, and he never reeked of wine. He evidently did not begin drinking until later, although hashish had already cropped up in his stories. He did not appear to have a steady girlfriend as yet. He never recounted amorous episodes from the past (which everyone else did). He never discussed mundane matters with me. He was communicative, not on account of his domestic upbringing but rather because he was at his creative peak…..

At this time he was busy working on a sculpture in the small yard next to his studio (in the deserted lane you could hear the echo of his hammer), dressed in his working clothes. The walls of his studio were full of incredibly tall portraits (they seemed to stretch from the floor to the ceiling). I have never seen any reproductions – did they survive? He called his sculpture ‘la chose’ – it was exhibited, I think in 1911 at the Independents. He asked me to come and view it, but at the exhibition he did not come over to me because I had not come alone but with friends. The photograph of this ‘chose’ which he gave me disappeared at the time I lost most of my possessions.

He used to rave about Egypt. At the Louvre he showed me the Egyptian collection and told me there was no point I see anything else, ‘tout le reste’. He drew my head bedecked with the jewellery of Egyptian queens and dancers, and seemed totally overawed by the majesty of Egyptian art. Egypt was probably his last fad. Shortly afterwards he became so independent that his pictures betray no external influence. Today this period is referred to as Modigliani’s Période nègre (Negro Period).

Commenting on the Venus de Milo, he said that women with beautiful figures who were worth modelling or drawing always seemed unshapely when clothed. Whenever it rained (it often rained in Paris) Modigliani took with him a huge old black umbrella. We would sit together under this umbrella on a bench in the Jardin du Luxembourg in the warm summer rain, while nearby slumbered le vieux palais a l’Italienne. We would jointly recite Verlaine, whom we knew by heart, and we were glad we shared the same interests….

It astonished me that Modigliani could find ugly people beautiful and stick by this opinion. I thought even then that he clearly saw the world through different eyes to ours. Everything that was fashionable in Paris and which attracted the most enthusiastic praise did not even come to Modigliani’s attention.

He did not draw me from life but alone at home. He gave me these drawings as a gift; there were sixteen of them. He asked me to frame them and to hang them in my room. They were lost in Tsarskoye Selo during the first revolution. The one that survived is less characteristic of his later nudes than the others.

We talked mostly about poems. We both knew a lot of French poetry: Verlaine, Laforgue, Mallarmé, Baudelaire. Later I met a painter who loved and understood poetry just as Modigliani did – Alexander Tyschler. That happens very rarely with painters.

He never recited Dante to me. Maybe because I still knew no Italian. Once he said to me: ‘I have forgotten to tell you that I am Jewish’. He told me straight away that he had been born near Livorno and was twenty-four years old. (He was actually twenty-six). He told me he had been interested in aviators (today we say pilots) but was disappointed when he met one: they were simply sportsmen. (What did he expect?)….and all around us raged cubism, all-conquering but alien to Modigliani….

Modigliani was contemptuous of travellers. He thought travelling was a substitute for real activity. He always carried Les Chants de Maldoror about with him. At the time this book was a rarity. He described how at Easter he had gone to early morning mass in a Russian church to watch the procession of the cross, since he loved ornate ceremonies. And how a ‘seemingly important personage’ (probably from the Embassy), had exchanged an Easter kiss with him. Modigliani probably never really understood what that signified…….

Once when I went to call on Modigliani, he was out: we had apparently misunderstood one another so I decided to wait several minutes. I was clutching an armful of red roses. A window above the locked gates of the studio was open. Having nothing better to do, I began to toss the flowers in through the window. Then without waiting any longer, I left.

When we met again, he was perplexed at how I had entered the locked room because he had the key. I explained what had happened, ‘but that’s impossible – they were lying there so beautifully’.

For a long time I thought I would never hear anything from him again……..but I was to hear a great deal of him……….’

In stating that Modigliani cared only for Egyptian art, Akhmatova unwittingly provides a fascinating, touching insight into his absolute single-mindedness. For we know that he was inspired by diverse cultures. And visited other museums. Akhmatova’s imminent return to Russia and Modigliani’s obsessive need to see her, during those few precious weeks together, as frequently as possible among the Egyptian queens and goddesses, so he might portray her in their guise, can be the only explanation for her claim.

From left to right: V Dynasty, The Louvre, Funerary Relief, 18th Dynasty, The Louvre

Many of the Egyptian reliefs, including those illustrated above, had been buried with the individuals they commemorated to accompany and comfort their spirits into the next world. This would have appealed to Modigliani’s mystical nature. And accorded with his ardent wish to celebrate, preserve and proclaim for all time Akhmatova’s beauty and timeless poetic spirit.

Indian 10th -11th century

Modigliani was also inspired by the beauty and sensual movement of the carved Indian deity dancers figures he would have seen at the Musée Guimet. The decorative ‘device’ of pearls strung sensually across the body may well have suggested the short pencil strokes subtly accentuating the sensuality of this drawing – particularly the left breast and thigh.

Perhaps the sight of the small, startlingly handsome young Italian and his tall, strikingly beautiful Russian companion, in fervid conversation filled with youthful hope, stopped a passer-by. As they sheltered close, cocooned and oblivious to the world, beneath a battered, black umbrella shielding them from the beating rain. And recited, in hushed, impassioned voices, to each other or in perfect harmony, the verses they knew by heart and loved so well.

And in the years to come. In the knowledge of the tragedy and triumph that awaited both, would he not have wondered at that moment?